Colorado’s crude oil production is surging, more than the state’s pipelines can handle. In order to increase capacity, shipping companies increasingly use railways to transport crude across the region, sometimes through crowded communities. And that can lead to accidents—as on May 9, when six cars derailed south of Greeley, CO, and spilled more than 5,000 gallons of oil.

While the damage in that case was fortunately limited, the transport of crude by rail is an important emerging story that’s attracting national attention. It’s also one that could tax many smaller news organizations: obscure government agencies, companies that prize secrecy, limited human-interest potential. But since the beginning of June, journalists at Inside Energy have been staking a claim to the crude-by-rail beat. Data journalist Jordan Wirfs-Brock traced the majority of crude oil and natural gas shipments to a single railroad, BNSF, while executive editor Alisa Barba and others reported on the lack of transparency in shipping routes, and the push for better disclosure. As befits a web-oriented startup, much of this coverage aggregated, amplified, and extended reporting that had appeared elsewhere, to good effect. All in all, not too shabby for a news organization that was created less than six months ago.

But Inside Energy isn’t a typical startup. It’s a partnership between public media stations in Colorado, Wyoming, and North Dakota focused on energy reporting, and one of seven Local Journalism Centers scattered throughout the United States.

Supported at launch by two-year grants from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the LJCs are designed to foster regional journalistic collaborations, and to allow local reporters to become authorities on subjects of national importance. They’re also opportunities for local public stations to figure out how to build something sustainable—both in content and in finances. After five years of trial and error and almost $16 million of investment from CPB, the projects are beginning to stand on their own.

The idea for LJCs first came up in 2009, when the news industry was in full-blown crisis and media thinkers were calling on public media to play a greater role. Bruce Theriault, senior vice president of radio at CPB, said it was clear that most individual public stations—both radio and television—lacked the staff and funds to deliver serious local coverage, and in some cases to do any original reporting at all. Alone, a community station in Binghamton, NY, or Monroe, LA, could hardly support a fully staffed newsroom.

But maybe it could support part of one—and if a few stations across a region teamed up, they could do high-quality work together. CPB put out a request for proposals that year and ended up funding an initial crop of seven projects to the tune of $10.1 million, or up to $1.5 million apiece. Each LJC would have its own beat. For Fronteras in the Southwest, it was immigration and the US-Mexico border; for Harvest in the Midwest, agriculture ruled; and for EarthFix in the Northwest, the environment was most pressing.

Inside Energy was born this past year in CPB’s second round of proposals, along with Pennsylvania’s Keystone Crossroads. The brainchild of Laura Frank, vice president of news at Rocky Mountain PBS, Inside Energy brings together Colorado’s CP12 television and KUNC radio stations, Prairie Public Broadcasting, Wyoming PBS, Wyoming Public Media, and Rocky Mountain PBS under a central editor: Alisa Barba.

“When I tell people I’m covering energy, their eyes glaze over, and you have to understand this is the issue of our time,” Barba said. “Without being too grandiose, we’re trying to focus on the nexus of people and the energy they use and the issues they need to understand going forward in a transforming energy economy. We’re looking at all kinds of stories and energy transformation as it’s changing these communities in Colorado, North Dakota, and Wyoming.”

Barba, formerly NPR’s Western Bureau chief, came to Inside Energy directly from editing Fronteras, based out of KJZZ in Phoenix. The lead editors are a central part of the LJC experiment, Theriault explained. “There aren’t that many editors in public radio, public media, at the local level,” he said. “A lot of people are doing their own editing. We were trying to increase the quality. When you have an editor, it’s not only listening to people and seeing what stories they should cover but editing the work, and you have higher quality storytelling.”

The goal, Barba said, is to ready the work of local stations for national—and even international—exposure. Stories from Fronteras have appeared on NPR, APM’s Marketplace, PBS Newshour, PRI’s The World, BBC’s Newsday and WBUR’s Here and Now (and those are the just English-language channels). Other LJCs have experienced similar success. At Inside Energy, Barba said, “Our plans are to ultimately become one of the key sources of information in the energy sector, especially in the center of the country.”

In their subject-specific focus, the LJCs share some similarities with both NPR’s Argo Network, which the CPB helped fund, and with the public radio networks’ StateImpact projects. The StateImpact model, although it didn’t expand as originally hoped, also puts collaboration at its core. So Philadelphia’s WHYY, the lead station in Pennsylvania’s Keystone Crossroads project, and Harrisburg’s WITF, a partner station, already had experience working together.

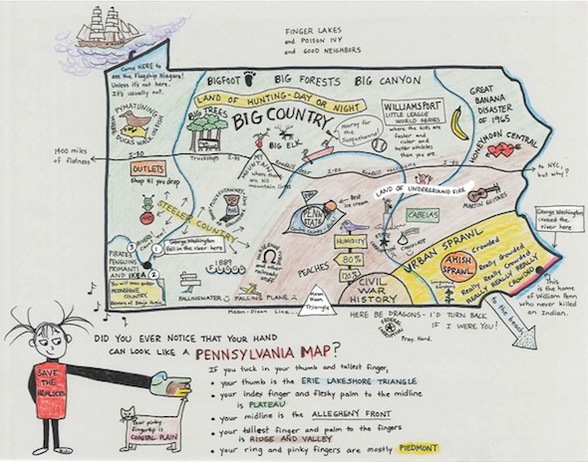

As part of its community engagement efforts, Pennsylvania’s Keystone Crossroads asked readers to draw their own maps of the Commonwealth. This one was sketched by Sue Shaffner of Rockton, PA.

As part of its community engagement efforts, Pennsylvania’s Keystone Crossroads asked readers to draw their own maps of the Commonwealth. This one was sketched by Sue Shaffner of Rockton, PA.

To cover other parts of the state, Keystone Crossroads also brings in Pittsburgh’s WESA and WQED and State College’s WPSU as partners. With the tagline “Rust or Renewal?” the project focuses its journalistic resources—four full-time reporters, a multimedia producer, a project manager, and an editor—on stories of urban transition in a former industrial center. The project mixes policy explainers and state budget factchecks with efforts to foster civic engagement, all against the background of a gubernatorial campaign. The broader goal is to foster a dialogue about urban issues that builds connections across markets.

“One of things we’re doing that local papers, by their nature, aren’t doing is connecting the lines between the cities in the state to see what are some solutions Philadelphia are looking out that Pittsburgh has done, and what do these smaller cities have in common, what are they trying, what’s succeeding, what’s failing?” said editor Naomi Starobin.

Those same questions—what is being tried, what’s succeeded, and what failed—are also being asked about LJCs by project managers around the country. Two of the original batch, Florida’s Healthy State and Changing Gears in the Midwest, effectively disbanded after their original two-year grant ended, with Healthy State absorbed by its lead station, Tampa’s WUSF.

As CPB’s Theriault tells it, the projects suffered from a lack of long-term planning, and the collaboration didn’t provide enough value to individual stations to continue. Healthy State’s emphasis on digital stories and social media meant too few pieces went on-air, he said, and the partners of Changing Gears had large enough newsrooms to not require a collaborative project.

In the second round, CPB and its grantees focused on avoiding those pitfalls and planning for the long-run from the start. Inside Energy spent some of its initial grant—which covers much, but not all, of an LJC’s operating expenses—to hire a full-time project manager, whose job includes securing funding and developing a sustainable business plan.

“We are, from day one, working on year three,” Frank said. “Some of things we’re looking at are events and forums, which some news organizations both inside and outside public media have had success with turning into revenue streams. We’re looking at products related to journalism and allocation models in which member stations would pay toward the overhead costs. We’re looking at multiple revenue streams that are gearing up now so they can be ready to take over.”

Innovation Trail, a first-round LJC founded in 2010 to report on technology and the economy in upstate New York, has made strides in bridging the gap between its initial funding and self-sufficiency. This past year, underwriters such as Iberdrola USA and Excellus Blue Cross Blue Shield insured that the project did not have to charge its member stations for the cost of its central editor.

In fact, Innovation Trail has become the foundation for a further expansion of public media in the region. Last month, CPB announced a $375,000 grant to help five stations create a single multimedia newsroom, known as Upstate Insight. Meanwhile, Rochester’s WXXI, the lead station in both Innovation Trail and Upstate Insight, received a smaller grant from the Knight Foundation to support Yellr, a mobile app for citizen journalism and data collection.

Sue Rogers, executive vice president and general manager of WXXI , said these initiatives would not be possible without the collaborative model. Small stations need help, she said—but they are committed to original local reporting.

“We don’t just want to be a pass-through for NPR,” Rogers said. “We don’t just want to be an also-ran part of the news landscape.”

Despite some hiccups, the results of the LJC experiment show that those journalistic ambitions can be achieved. For any individual project, the challenge is to meet that editorial target while also grappling with the bigger question: Can it last?

“That,” said Frank, “is the million-and-a-half dollar question.”

Archives:

Archives: