We’re still almost three years away from November 2016, but political journalists seem to want to fast-forward past the ongoing Washington stalemate to the next presidential election. How else can we explain the recent flurry of coverage for trial heat polls, which pit possible presidential contenders against each other in hypothetical general election matchups?

There’s just one problem: These polls—which exist mainly to generate press coverage for pollsters and fill space in the media—have zero predictive power at this point in the election cycle, don’t tell us anything we can’t learn from other metrics, and distract attention from the real action at this stage of the campaign.

The most recent example of a clickbait trial heat poll comes from a Quinnipiac survey showing Hillary Clinton leading Paul Ryan, John Kasich, and Chris Christie in Ohio. The poll was reported by The Columbus Dispatch Thursday, though, to his credit, reporter Joe Vardon prefaced his blog item on the survey with the disclaimer, “We’ve got a while until it matters.” These caveats were not present in a a Cleveland Plain Dealer report on the survey, which devoted more than 300 words to parsing its polling on the 2016 race.

Presidential trial heats like this one have been all over the media in the last few weeks, including a Quinnipiac poll in Colorado (Rand Paul leads Hillary!), a PPP poll in Louisiana (Jindal barely beats Hillary in a red state!), and national polls by McClatchy-Marist, CNN/ORC, and Washington Post/ABC (Hillary’s lead over Christie has grown!).

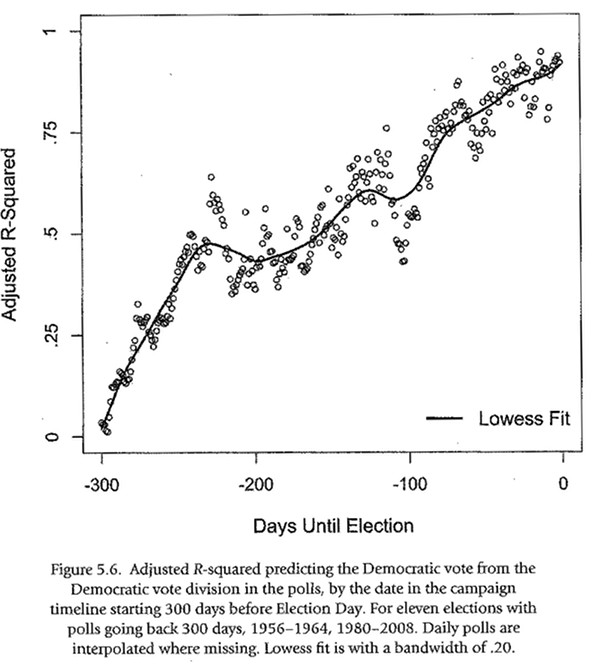

These matchups may be fun to speculate about, but the evidence suggests that even national trial heat polls conducted this far in advance of a presidential election are completely uninformative about its outcome. (Individual state trial heats are likely to be even less useful.) In their book The Timeline of Presidential Elections, the political scientists Christopher Wlezien and Robert Erikson find that polls conducted even 300 days before an election have virtually no predictive power; their forecasting power comes later in a campaign:

Just as a reminder: We are currently 990 days away from the 2016 election.

A review of early trial heat polls from recent elections shows just how inaccurate they can be. For instance, polls showed John McCain consistently leading Barack Obama in hypothetical matchups in late 2006 and early 2007, but the Republican lost the popular vote to the Illinois senator by 7 percentage points in 2008. Obama led Mitt Romney by 12 points in January 2010 (he won by 4), while George W. Bush ran 13 points ahead of Al Gore in March 1998 (he lost the popular vote by 0.5 points). Back in October 1991, Bill Clinton attracted just 22 percent support (including leaners) in a NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll matching him up against George H.W. Bush, but Clinton defeated the incumbent president by six points a year later in a three-way race with Ross Perot. By contrast, Ronald Reagan was found to be in a statistical tie with Walter Mondale in a March/April 1982 Harris survey, but went on to destroy the former vice president in an 18-point landslide in the 1984 election.

As a general rule, candidates with high name recognition and favorable public profiles often appear formidable in these early polls, but campaigns serve to remind people of the state of the country and their partisan loyalties. As a result, candidate quality matters less than most journalists assume (see: John McCain’s transition from bipartisan hero to polarizing partisan), and the economic fundamentals—which can’t be known at this early date—matter much more. And while trial heats may have some limited value as a snapshot of a candidate’s standing with the public, simple polling statistics like a politician’s favorable/unfavorable numbers are easier to interpret and comparable with a longer time series of historical data.

More generally, the focus on trial heats obscures the real action in the 2016 campaign right now, which is taking place within the parties as potential candidates jockey for support among the elected officials, activists, and donors who will help determine the eventual nominees. As the political scientist Jonathan Bernstein wrote on Bloomberg View, “All presidential candidates should be thinking about just one thing right now: the nomination.” The invisible primary may be harder to poll than trial heats, but it’s also much more informative about who may be occupying the White House after 2016.

Historical polling data was drawn from the iPoll archive of the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research.

Archives:

Archives: