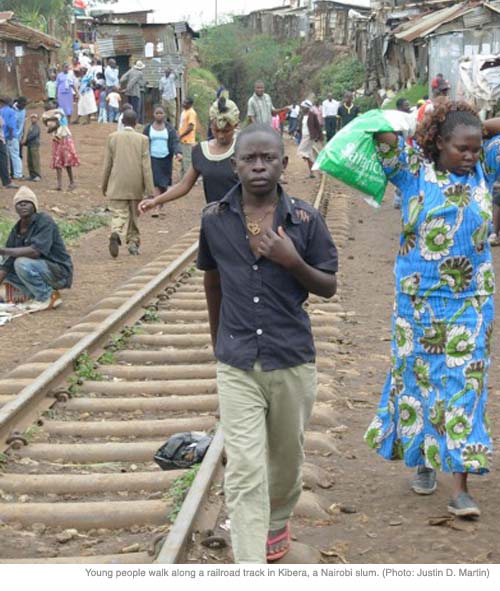

NAIROBI, Kenya—Before landing in Kenya, my doctor had me get shots for typhoid, tetanus, cholera, yellow fever, and meningitis. He also gave me malaria pills. One in every fifteen Kenyans has AIDS. Nairobi is home to Kibera, one of the world’s most disease-rotted slums.

Yet there’s not much of a push for medical journalism in Kenya, a nation that sorely needs it.

One 2009 report from researchers at Zurich University wrote that, in Kenya, “[m]ost interviewees from media companies—journalists, editors, managers—confirmed quite frankly the limited importance and low quality of health reporting. As the main reason this group of interviewees highlighted the general political orientation of most mass media.” The report went on to say that scholars studying Kenyan media have found that more than 70 percent of all news content focuses on politics.

Birth of a Nation is Gerard Loughran’s gripping 2010 biography of The Nation newspaper, Kenya’s most storied and successful daily. That history, though, chronicles the newspaper’s political battles and coverage, yet contains scant details of The Nation as a magnifier of Kenya’s grievous health problems, or an amplifier of solutions.

Kenyans are voracious news consumers. They “rely on news—and on God—to help them through their woes,” according to a news executive for one Kenyan TV network. Even as circulation of newspapers declines in many countries throughout the world, print dailies in Kenya are everywhere. In a piece for CJR, Karen Rothmyer marveled at “how highly prized newspapers still are [in Kenya]—at a time when they’re dying like flies in the U.S…Its nearly 40 million citizens, both middle-class and otherwise, have a seemingly unquenchable passion for print.” Each time I paused at military checkpoints while traveling outside the Kenyan capital, soldiers asked me if I had a spare newspaper I was done reading.

News outlets independent of the Kenyan government are allowed to operate and thrive, and while Kenya is no reporter’s paradise, the country has one of Africa’s more free presses. Freedom House specifically praised Kenya in its 2011 press freedom report as one of a handful of nations that made the most advances in media freedom in the prior year.

Relevant health reporting can have a powerful impact in Kenya, as anywhere else. Researchers reported (pdf) in the 1980s in the journal International Family Planning Perspectives a strong association between exposure of Kenyan women to media messages about contraception and their likelihood to use birth control. This study was undertaken over twenty years ago, yet Kenya’s population is still growing far faster than the rate of replacement and much too fast for the country’s good.

One barrier to increasing medical reporting is overcoming publishers’ and producers’ skepticism that such news is lucrative, a common frustration of public health researchers and officials.

Medical reporting shouldn’t be that tough of a sell; nothing catches the ears of news consumers like information about their children’s schools or dangers to their family’s health. Health reporting is also often less likely to draw government ire, like reporting on bribery and graft. Corruption benefits the greased, but malaria benefits no one. “Malaria keeps countries poor, and because they are poor the potential market for a vaccine is not sufficiently valuable [for] drug companies,” wrote Paul Collier in The Bottom Billion.

“Journalists must make the significant interesting and relevant,” wrote Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel in The Elements of Journalism. “Storytelling and information are not contradictory.” It’s up to Kenyan journalists to spotlight public health problems in ways that turn the public neck.

Medical journalism may be of particular benefit to African countries like Kenya, due to the fact that outside development models in this part of the world often fail. “Anybody traveling in Africa can see that aid is much harder to get right than people realize,” wrote Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn in 2009, and “involves tinkering with the culture, religion, and family relations of a society that we often don’t fully understand.” Simple aid “does not work so well in [many of] these environments,” adds Collier. “Change in the societies at the very bottom must come predominantly from within.”

It may seem logical to pay rural women in Kenya fifteen dollars to give birth in an urban clinic, for example, but encouraging Kenyan broadcasters to cover common stories of the horrors of rural labor may be considerably more effective. One reason The Nation newspaper in Kenya has been a profound success is because its white founders expressed immediate intentions to “write themselves out of their jobs,” according to Loughran, and build a newspaper written and run by black Africans. And they did, helping to create one of Africa’s most vibrant news markets.

Kenyan journalists don’t need to be told how to report the news, but it does appear that some of the country’s most severe health problems aren’t receiving proportional media attention.

While in my hotel room in Nairobi, I watched a lengthy news report on poor Kenyan women who toss newborn babies in a well-known garbage dump. Some of the babies are found and taken to orphanages with the hope of finding adoptive parents. The rest rot to death in the landfill. I’ll probably never forget that news story as long as I live, but that’s because the report was on TV and it was in English. To reach most of Kenya’s abject poor, those who are dropping newborns in baking garbage, the report would need to be on radio and in Kiswahili.

On a 1950 visit to Kenya, one British diplomat said, “This is God’s own country with the devil’s own problems.” It still may be, and Kenya’s public health challenges, not just its political battles, are among the country’s nastiest ills. In the world’s poorest places, political corruption isn’t the devil’s only pall.

Archives:

Archives: