News organizations can be forgiven for feeling that they’re in an endless cycle of Whac-A-Mole.

News organizations can be forgiven for feeling that they’re in an endless cycle of Whac-A-Mole.

They’ve had fifteen years to get onto the Internet, and for much of that time the experience was limited largely to words and photos on a web page, accessed on a personal computer. But more recently, journalism has been blessed and bedeviled by a stream of follow-on innovations. As a result, most organizations have tried to develop new ways to report and distribute stories, and many are making substantial investments so their work will appear on attractive new devices. Their hope is that these new kinds of digital journalism will enhance companies’ earnings; their fear is that if they don’t adapt, they will lose audiences’ attention and the revenue it brings.

It hasn’t been easy. Video has been seen as a great way to get more sustained engagement, but many news organizations have found it to be expensive and difficult to produce. And even though ad rates are three to five times what regular display ads bring, video often doesn’t get enough traffic to attract substantial revenue. Mobile devices, meanwhile, provide consumers with greater access to news, but the small screen size can be a nightmare for designers and a poor display space for advertisers.

Tablets—particularly the iPad—have looked like a more immersive experience for readers, and a more likely venue for subscriptions and higher ad revenue. But their luster has dimmed as the dominant manufacturer, Apple, has insisted on charging high fees and controlling economically valuable information about customers. Each new device brings an additional level of complexity and expense. Not long ago, “convergence” was the keyword in news production, as television, newspaper, magazine, and pure online sites all started to look the same. Now comes a new “divergence,” in which online journalism organizations must distribute news into distinctly different modes of presentation.

The iPad has been a hit: Expectations are that about thirty million devices will have shipped by the end of 2011. But while analysts expect the iPad to capture more than 90 percent of the tablet market in 2011, competitors are entering the fray. Tablet manufacturers have announced that more than twenty-five brands will be available in 2011, at screen sizes ranging from five to eleven inches.

Audiences are fragmenting in other ways, too—in their interests and habits. The conflict is evident in the behavior of Michael Harwayne, vice president of digital strategy and development at Time Inc. Harwayne lives in Manhattan and takes the subway to work. He likes to read The Wall Street Journal on his commute, but lately the question has been: Which format works best?

Harwayne likes the Amazon Kindle. When the Journal became available on that device in the spring of 2009, he decided to pay an extra $10 per month for the convenience, though he was already paying $363 per year for the print and web editions. The Kindle price rose to $15 per month a year later.

But there was no connection between his print/online subscription and the Kindle edition, and Harwayne found it annoying to be billed separately. Then, in May 2010, came the Wall Street Journal iPad app, which he got as part of his overall subscription. It’s not that it was “free,” but because he didn’t have to pay a separate fee, it felt free. Still, he said, “I didn’t like carrying it and reading it on the subway, so I never actually canceled the Kindle until I had a lightweight alternative.”

In the fall of 2010, he was introduced to a Samsung tablet. He liked it more than the iPad, so he switched to the Journal’s Android version (which is also included in his core subscription to the paper) and finally canceled his Kindle subscription. But Harwayne wondered, “Why shouldn’t I be able to read the paper on any device I have?”

In March 2011, he learned that he’ll eventually have to pay an additional

$17.29 a month to keep his iPad or Android version of The Wall Street Journal. Through it all, the one thing that hasn’t changed is that Harwayne likes to read the print version of the Journal after a long day at work. Still, it “seems like a very strange consumer strategy,” he says.

Early data about tablets appeared to show great promise for news organizations. A few months after the first iPad went on the market in the spring of 2010, the Associated Press reported that Gannett Co. was getting $50 per thousand page views for iPad advertisements—or five times the price it was getting on its websites. Condé Nast initially said visitors were spending an hour with each of its iPad issues—far more than the three or four minutes per visit its websites draw and close to the overall print magazine average of seventy minutes. David Carey, president of Hearst Magazines, said in March 2011 that the company would end the year with “several hundred thousand subscriptions in total” sold through digital publisher Zinio, Barnes & Noble’s Nook e-reader, and Apple’s iPad. He predicted that as much as 25 percent of his company’s subscribers will be on tablets “in the next five years.”

But making predictions based on early and volatile sales is tricky. The data on usage of tablets and smartphones come from products—and a competitive environment—that are in transition. Many buyers are early adapters to technology, a group whose behavior does not reliably predict the greater population who will eventually buy the gadgets. (Of the 66 million smartphone users in the U.S., only about a third have used the browser or downloaded an app, according to audience measurement company comScore.)

Wired, a magazine with a tech-savvy readership, sold 100,000 single copies via the iPad in June 2010, but that number dropped to 22,000 by October; in 2011, its single-copy iPad sales have averaged 20,000 to 30,000 per issue. Wired’s average monthly circulation of 800,000 still consists mostly of print subscriptions and single-copy sales; a small number (27,000) are sold as PDF-based digital replicas. It’s likely that the high price and one-issue limit of Wired’s iPad version have hindered sales; one copy costs $4.99—the same as a copy sold at the newsstand—while an annual print subscription starts at around $12 a year. And the froth has settled throughout its parent company: In April 2011, a Condé Nast publisher told AdAge that the company’s iPad strategy was slowing: “They’re not all doing all that well, so why rush to get them all on there?”

One issue is Apple’s own pricing strategy. The company announced in early 2011 that it wants a 30 percent cut of any subscriptions paid through the iTunes store. More important, when the user pays with a credit card stored in iTunes—and Apple had about 200 million registered users in 2011—the user’s name and address don’t have to be shared with the publisher, unless the customer agrees. Without this information, publishers have a handicap: They can’t find out the particulars of their subscribers’ reading behavior. Google is pushing an alternative tool for subscriptions called One Pass, in which the company will charge publishers 10 percent of revenue and share subscribers’ names and information. Some publishers, such as Time Inc., have built their own payment and collection systems for selling their own apps from their own websites so they don’t have to share any information or pay any fees.

For most magazines, neither the replica digital copies nor the iPad versions of their magazines count in the “rate base,” which is the number of readers publishers guarantee to deliver to advertisers. So, for now, publishers tout it as “bonus” circulation they can’t really charge for.

Some news organizations are optimistic about the economics of mobile devices. In March 2011, Dow Jones announced that it had 200,000 paying subscribers who access to The Wall Street Journal via some sort of mobile device. The company did not say how much additional revenue this brought in, so many of these readers could be like Michael Harwayne—digital subscribers who signed up for mobile access. (The Wall Street Journal’s total reported average daily paid circulation is about 2 million copies—1.6 million copies in print and 430,000 electronic copies.)

Time Inc. announced plans in February 2011 to give Time, Fortune, People, and Sports Illustrated subscribers the ability to access those magazines’ content on multiple platforms. Sports Illustrated has been particularly aggressive in digital expansion; to introduce its digital package as widely as possible, it has given access to all 3.15 million of its current print subscribers. For new customers, it is promoting an “All Access” subscription plan, which includes the print magazine, plus access via tablet, web, and smartphone; in March 2011, the price for All Access (including a bonus windbreaker) was $48 per year. A digital-only package with no magazine and no jacket costs the same. That pricing scheme helps protect the print edition and provides the biggest possible digital audience.

Some publishers are willing to invest a lot to gamble on an unknown future and avoid sitting on the sidelines.

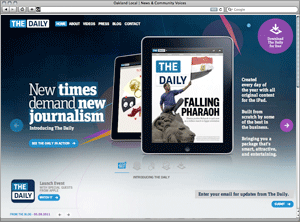

In February 2011, News Corp. launched The Daily, a tablet-only newspaper. First offered on just the iPad, though there are plans to extend it to more tablets, The Daily announced a start-up budget of $30 million, which let it hire enough journalists, designers, and technicians to create 100 pages of content per day. Integrated into The Daily are features that seem to shine on the iPad platform, such as social-media links, audio, and video. Greg Clayman, publisher of The Daily, said hundreds of thousands of users have downloaded the app, but he’s not ready to reveal how many use it on a regular basis.

George Rodrigue, managing editor of The Dallas Morning News, says the iPad “may be the thing that helps people read enterprise journalism. We used to say you have to be platform agnostic. I don’t think that’s right anymore. You have to be platform specific.” But the transition isn’t cheap. “We have to build a staff for the iPad—two people plus an assignment editor,” he says. “We’re going to handcraft little stories summarizing every story—fifty-five words max. Every reporter will write the summary themselves. Every section front will be a summary of the news page.” At The Miami Herald, Raul Lopez, the interactive general manager, estimates the paper’s total digital page views to be 30 million per month; about 2 million are mobile, and half of those are via the iPhone.

Meanwhile, video has become an essential element of the digital experience. According to comScore, about 89 million people in the U.S. watched at least one online video, or video advertisement, daily by the end of 2010.

For journalism sites, broadband access has made video distribution more feasible. But persuading users to watch news video isn’t easy. Online video journalism is becoming a world of haves and have-nots. Among the haves, CNN.com reigns supreme.

“In any given month, well over half our unique visitors watch video,” says K.C. Estenson, senior vice president and general manager of CNN.com. “The percentage has gone up every year.” When CNN.com redesigned its site in 2009, the network “anchored it on video,” Estenson says. It isn’t unusual for the website to have fifteen or more video links on its home page, including at least three or four in high-profile featured positions.

CNN.com is different than other video-rich sites because of the size and expectations of its audience. The company says it delivers between 60 million and 100 million video streams a month. In contrast to local-broadcast competitors, CNN.com can match the costs of substantial technology and editorial costs with a massive audience. “If you do not have scale, you do not have a business,” says Estenson. CNN.com has also launched a free iPad application in which video is integrated into text. And CNN is hungry for more viewers. Estenson says CNN can sell “almost every single video impression we create. So we would like more video consumption.”

CNN has brought its broadcast expertise onto the web. “We program by times of day,” says Estenson. “The bell curve of visitors to our site peaks between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. on regular news days. We’ve noticed that social media links go up a lot at night.” Sometimes CNN makes programming decisions based on a mix of demographic and editorial priorities. Estenson notes that users under the age of twenty-five, who “are disproportionately on social media,” tend to be more interested in entertainment and features rather than in hard news. So while “CNN is all about trust and reliability,” Estenson says, “for CNN.com, entertainment is one of the biggest sections of the site.”

Estenson sees contrasts between the content on CNN’s cable channel and CNN.com. Online, producers have more freedom to experiment and expand, and the content can be more daring. “Going online is a private experience, versus watching in the living room. When people are online, they seem to gravitate to things that are more provocative than they would if they were in a room with their friends.”

How profitable is CNN online? According to a presentation the network made to analysts in mid-2010, revenue for CNN overall (consisting of the U.S. and international divisions, Headline News, and digital) was about $500 million; digital advertising and content sales accounted for about 10 percent of total revenue. CNN.com’s profit margin isn’t broken out publicly by either its division, Turner Broadcasting System Inc., or by the parent company, Time Warner Inc. Estenson does say the digital operations have been profitable for the last seven years—even including corporate costs and just under 100 “dedicated digital” people on the editorial side. All of CNN benefits from a centralized publishing platform; sales and administrative expenses are spread across the three television divisions and their online properties.

CNN.com is dependent mostly on ad revenue that is sold directly by a CNN sales force. But the digital business also gets some direct corporate support. Estenson says a “select portion” of the subscription money that cable and satellite companies pay to carry CNN’s programming is used for research and development activities related to new technologies, such as smartphones, tablets, and televisions connected to the web. Thus, benefits from CNN’s digital investments flow both ways, from the traditional to the digital and back.

Estenson believes the site feeds viewers and value back to the legacy network. “Digital platforms are the entry point for the brand. More and more people will discover the brand through them,” he says. And he envisions some of the distinctions between the two platforms becoming less relevant, especially as the Internet gets a bigger foothold in living rooms.

CNN.com is something of an exception in its success with online video. Most local TV stations’ websites have far less traffic and revenue. In interviews with executives at a station based in one of the top five metropolitan areas of the country, a more difficult picture emerges. (The station was willing to share metrics on the condition it not be identified.) In October 2010, the station’s website attracted about 7 million page views. But it delivered only 622,000 video streams that month. The station’s general manager said that when video became feasible on the web several years ago, executives believed they would have a natural competitive advantage. “We thought having video was the key to becoming a popular website. But only 10 percent of the visitors look at video.” And partly as a result of the low video usage online, only 1 percent of the station’s total advertising revenue comes from its website.

The general manager has seen statistics that show similarly paltry results at other local television stations’ sites. One problem, he says, is that other sites are also producing video, so broadcast stations face more competition for views. Sports fans appear to be particularly interested in newspaper sites’ video. He has thought about doing more consumer research but can’t justify the expense. “No one is buying the site, really,” he says, “so it’s not worth spending more money to figure it out.”

Somewhere between this station’s frustration and CNN.com’s success is LIN Media, a company that owns thirty-two local television stations in markets ranging from Springfield, Mass., to Albuquerque, N.M. LIN’s sites delivered 116 million video streams in 2010, and has built its business on shared operations and costs, as well as long-term investment in branding and marketing.

LIN is in seventeen markets, and the company has multiple stations in several cities. It is in small- or medium-sized “DMAs”—that is,“designated market areas” that are defined and ranked by Nielsen, the audience-rating company. The markets range from Indianapolis (twenty-fifth largest in the country) to Providence, R.I. (fifty-third) to Lafayette, Ind. (191st). LIN controls costs by having one building, one staff, and one newsroom per market, with costs shared by all its stations in that market. For non-local topics such as health, LIN produces stories that serve all of its markets. Companywide, LIN has about 200 digital employees in a workforce of 2,000. (Four years ago, it had nine digital employees in a workforce of 2,300.) Robb Richter, LIN’s senior vice president for new media, says the video the company produces for broadcast is its competitive advantage. “We have mounds of video we can use”—something most other sites lack.

Print-based media are still building video resources and expertise. Even those with successful sites have had a hard time winning a video audience. Michael Silberman, general manager of New York’s popular site, says nymag.com has tried to integrate video into its editorial content but that the pace of video and the commitment to watch it still aren’t working for most visitors. The site features videos it produces in-house as well as material from around the web that is “curated” by online editors, based on subject matter, relevance, and news value. So, for example, nymag.com has a food video page with categories beyond news, such as restaurants, chefs and recipes. But it’s hard to build an audience, Silberman says, adding, “If your site isn’t about video, people don’t click on it.” For nymag.com, less than 10 percent of unique users go to video. At The Huffington Post, no more than 5 percent of unique visitors clicked on a video throughout most of 2010.

Lewis DVorkin, chief product officer of Forbes Media, agrees. “Video on the web is hard. It’s very stressful,” he says. Since joining Forbes in the spring of 2010, DVorkin has been coming up with new ways to create and distribute Forbes content. But video has him stumped: “We had a difficult video strategy. It was conceived on the broadcast model—produced, highly expensive, and it involved lots of people.” He foresees moving to outside contributors more in video, as he has done elsewhere on forbes.com. DVorkin and nymag.com’s Silberman both say that until they unlock the video puzzle, they are losing opportunities for ad revenue. Silberman says, “Our ad demand outstrips our audience demand.”

The Wall Street Journal’s site has drawn significant traffic and revenue to its video offerings. The site serves around 8 million streams a month, says Alan Murray, deputy managing editor and executive editor, online, for the Journal. And the ad rates are healthy—$30 to $40 per thousand views (or CPMs). The site features live videos before and after the market closes, and they’re often displayed prominently on the home page. Unlike much of the rest of the site, viewing the videos doesn’t require a subscription.

The key to making video profitable, Murray says, is controlling costs. WSJ.com has about sixteen people devoted to video production, and the company has trained many of its print reporters in basic video techniques. “If you go to Bahrain and need a satellite truck, that’s $25,000,” Murray says. “All we need is a $200 iPhone 4.” WSJ.com has also managed to get viewers to watch video during work hours, something that many other sites have found difficult.

The Miami Herald recently noted that its video traffic grew by 25 percent in 2010. Videos that the Herald produces and hosts on its site get about 200,000 streams a month, says Lopez, the interactive general manager. That is a relatively small number, given that the site gets more than 6 million visitors per month.

The Herald has bolstered its video presence with segments produced by the Associated Press and other organizations. It also tried to distinguish itself by producing longer videos of newsmakers talking about various topics, but those are a tough sell online. “There’s a reason that television does two-minute stories,” the Herald’s managing editor, Rick Hirsch, told Poynter.org. “Unless something is super compelling, people’s attention span is relatively short, and it’s even shorter on a small screen.” And it’s not easy to make the advertising numbers work. Lopez says Herald-produced videos earn just $4,000 per month—that is, 200,000 streams a month at $20 per thousand viewers.

Cynthia Carr, senior vice president of sales at The Dallas Morning News, also doubts video will become a significant profit driver any time soon. “We’re not monetizing video. I don’t see that bringing big revenue,” she says. Dallasnews.com got an average of 186,000 video streams a month in 2010, clicked on by 2 percent of the unique visitors coming to the site.

And video traffic is hard to anticipate. Like Hollywood, there are hits and flops—as the Detroit Free Press found in January 2011, when it ran a dramatic video of a shootout in a local police station. It got nearly 714,000 streams, or nearly half the total traffic to video on Detroit’s site for a three-month period. When it launched, the video was preceded by a short commercial. But within seven hours and 70,000 streams, a reader who went by the name “HartlandRunner” posted this comment: “I am glad you are willing to tell this story by showing the video, but why the ad beforehand? Brutality brought to us by UnitedHealth Care? …Very, very tacky, even in an online world.… This tape was paid for by taxpayers and shows graphic real violence… and you guys put an ad on it. That’s unbelievable and I hope you change it.”

Nancy Andrews, Detroit Free Press’s managing editor for digital media, said, “I saw the comment and checked with the vice president of advertising. She said let’s take the ad off.” So they removed the ad, and forfeited some revenue—but kept readers happy. And it did help editors understand even more about how news video works on the Internet. “People are interested in the raw video content,” Andrews says. “Show me what happened.…You don’t necessarily need the context in video form, too.… Think of it more like a picture that talks than a full story.”

To continue to Chapter Five, click here.

To download this chapter as a PDF, click here.

Archives:

Archives: