The Seaton family had spent four generations weaving a daisy chain of newspapers across the small towns of the plains states. By the 1990s, they were ready for something bigger. The climate was good. Profits rained upon them. But in those heady days, the sun shone on the whole industry, and large media outfits and investment firms had developed a big appetite for small papers.

From its headquarters at The Manhattan Mercury in Manhattan, Kansas, the Seaton Publishing Co. lost bids for newspapers in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; Stevens Point, Wisconsin; and Ames, Iowa—all to bigger players. “We made bids on papers we thought were attractive and just got swamped,” says Ned Seaton, the managing editor of the Mercury, which his family has owned since 1915. “We weren’t anywhere close.”

In 2007, Ned received a query packet from the newspaper brokerage firm Dirks, Van Essen & Murray containing the financials for The Daily Sentinel in Grand Junction, Colorado, which had just been put up for sale by the media giant Cox Communications. The Sentinel, with a circulation of 25,000, would have been the biggest addition to date for the Seatons. (Their flagship Mercury hovers at around 10,000). Ned ran the numbers and figured that a winning bid for the property would be beyond their means. He threw it in the trash.

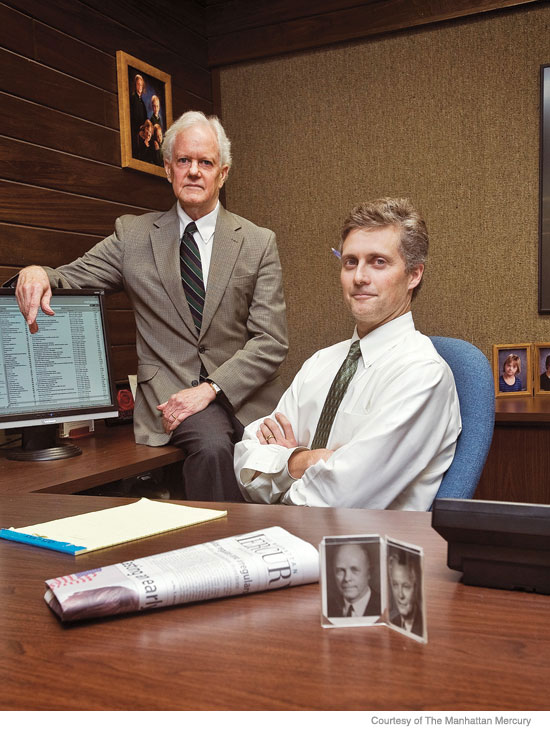

By the end of 2008, however, the Grand Junction paper was theirs—at a price they could only have dreamed of a year earlier. “There was still a decent amount of risk,” Ned says, “but we felt like we got a great deal.” Ned, forty-three, a cautious reporter-cum-businessman with a Harvard degree, had returned to small Seaton Publishing with some reservations in 1996 after working for the likes of The Associated Press, The Orange County Register, and the St. Petersburg Times. Now he is thankful he made the move. His father, Ed, is the boss, but Ned more or less maps the company’s strategy. He is lean and unpretentious, and so is the Seaton operation. Their building is forty years old and largely windowless. The full-time editorial staff of fifteen toils on old computers bubbling with tube monitors. Some reporters—typically fresh out of college and working for little—use their own laptops. Faded pictures of Ned’s forebears rest atop a bookshelf, reminders of his heritage as a newspaperman. Nearby are reminders of the future: photos of his three children.

Unlike many of the folks he left behind at big outfits, Ned has reason to feel good about where the business is going. That’s because the great crash of 2008-2009 has had an unexpected upshot: a second act for the family-owned newspaper. These smaller newspapers’ price tags are shrinking as the large buyers abandon print. “The past year and a half we’ve seen a number of family owners step forward and buy papers at very attractive prices,” says Jamie Oldershaw, a senior vice president at Dirks, Van Essen & Murray, the country’s leading newspaper merger-and-acquisition firm.

Faced with loads of debt from newspaper buying sprees over the years, declining ad revenue, and a future fogged by the Internet, some corporate owners are unloading newspaper properties as fast as they snatched them up. Cox Communications held a fire sale in 2009: dropping thirteen papers in North Carolina, two in Texas, and Colorado’s Daily Sentinel. The buyers? Private owners, including the Seatons; insurance magnate Clifton Robinson, who is now the local publisher of his hometown Waco, Texas paper; and billionaire John Kent Cooke Jr. The New York Times Company, meanwhile, unloaded the Times Daily in Florence, Alabama, to the local Shelton family. In Minocqua, Wisconsin, the Walker family purchased a neighboring paper from BlueLine Media Holdings, which is backed by private equity money, to complement their Lakeland Times. And Sample News Group, led by George “Scoop” Sample, recently took three papers from community paper colossus GateHouse Media. And so on.

In total transactions and dollars, these sales are a relative pittance. In 2010, thirteen dailies were sold for a total of $148.9 million. Compare that to 2008, when total deals were worth $833.5 million—largely due to one big transaction, the Tribune Company’s Sam Zell moving Newsday to Cablevision for $650 million. But it’s the very absence of those large sales that has come to define the new newspaper world. Big is no longer beautiful. Major metro dailies are facing competition for advertising revenue and audiences. In small towns, papers have loyal audiences and less competition among advertisers. The demographics are right, which basically means the residents are old—less interested in getting news from Gawker and more interested in getting it off the front porch. That’s partly why last year more than three-fourths of the newspapers that found buyers had circulations of less than ten thousand. Those types of papers are making money—even now.

In the 1990s, Dirks, Van Essen & Murray was negotiating sales of papers at ten times (or more) annual earnings—twice what they’re going for today—because newspapers were making incredible profits, 25 to 35 percent or more. Corporations wanted in; plenty of family owners got out, making a bundle, thanks to easy credit for corporate borrowers.

Investment firms saw opportunity in small and medium towns, and they fueled companies such as GateHouse Media and American Consolidated Media, which consolidated much of the community newspaper market. The Seatons and, for that matter, the Walkers and the Sheldons and plenty more would have had to leverage their businesses to the brink to compete. So they stood pat. Brown Publishing Company, of Ohio, is one who got in the game. It was aggressive and wound up with a portfolio of dozens of weeklies, dailies, and business journals in Ohio and other states. Then it went bankrupt. American Consolidated Media, which owns about a hundred small newspapers, also crashed.

The people buying today are the little guys who were squeezed out in the go-go days of yesteryear and didn’t bury themselves in debt. Murray Cohen, who claims a constellation of small papers across the Midwest, is one of them. For years, he coveted the county-seat paper in Van Wert, Ohio, next door to his flagship paper, the Delphos Herald, but it belonged to the muscular Brown Publishing. Last year, Cohen finally got the Van Wert Times Bulletin—and two others—at Brown’s auction. Aside from a small paper in Michigan, the Times Bulletin was his first significant acquisition in twelve years. “We bid on a number of papers and we were the unsuccessful bidder,” Cohen says, “so when the recession hit, the prices became more realistic.”

Cohen is eighty-one years old. He’s ridden out more high times and more low times than just about anyone in newspapers. “There hasn’t been a recession yet that has bothered us,” Cohen says. “Including the last one.” That can be said of a lot of small papers. Their relationships with advertisers and readers are intimate. Craigslist is less of a threat. Frequently there are no local television stations to compete for ad revenue and news. Staffs are lean. Some of the papers are so small there’s only one full-time employee. With credit now tight, many are getting loans from local banks to fund new acquisitions—also the result of relationships. While the days of 35 percent profits seem to be gone, small newspapers (which are privately owned and don’t have to report earnings) say they are still posting healthy returns.

The Seatons of today—various members of whom own papers in Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and most recently, Colorado—believe they’ve survived because they hewed to the basics. They focus intensely on local news and believe readers reward them by maintaining their subscriptions. Kansas State University and the local Army base, Fort Riley, sustain the town and the Mercury’s numbers. Circulation levels may also be aided by the subscriber-only website. (Because of the competition for readers, K-State sports stories are free.) Craigslist has decimated the paper’s classifieds, nullifying college kids as a source of revenue, but Manhattan has no local television affiliates. So if you want the news in the Little Apple, you’re going to have to pay the Mercury for it. And local news is what you’ll get.

The March 2 issue of the Mercury featured one front-page AP story, but only because it concerned Fred Phelp’s notorious gay-hating Westboro Church, which is in nearby Topeka. In that morning’s budget meeting, Ed and Ned Seaton and two senior editors discussed the census, the school-board budget, and a nearby animal science lab. They anticipated complaints from certain local big wigs, and discussed the recent Rotary meeting. They also got word that day that the Mercury had won thirteen first-place Awards of Excellence from the Kansas Press Association for 2010 across a field of writing, editing, and photography categories.

Archives:

Archives: