In CJR’s second issue, William L. Rivers presented a survey-data heavy article analyzing the Washington press corps. Rivers’s study was an update of The Washington Correspondents, a similar 1937 book. He argued that D.C. reporters were more professional than their counterparts three decades earlier, less likely to believe that their copy was subject to publishers’ political whims, and more likely to be paid far above an average worker’s wage. For today’s readers, it offers a snapshot of reporting in the age of Kennedy’s Camelot, and shows the continued dominance of some outlets (over 80% of reporters said they relied on The New York Times) and the absence of others (the most praised magazine was The Reporter which folded in 1968). Rivers’s article, based on thesis research, was expanded into The Opinion Makers, a book published in 1965 by Beacon Press, and hailed in the Political Science Quarterly as a “refreshingly candid look at some of the kingpins of American journalism.” The below paragraph originally ran above the article.

It has been said that most scholarly research is superseded within twenty years. By that criterion, Leo Rosten’s The Washington Correspondents has held up remarkably well. Still, a quarter of a century has brought major changes in the capital press corps. A broad new study of its composition was needed—and has been done. The author, who was twelve years old when Rosten’s study was published, did much of his research while working in Washington as a correspondent for The Reporter magazine and earning a Ph.D. in political science at American University. Before that, he worked on newspapers in Louisiana and Florida and contributed articles to many magazines. He is now an associate professor of journalism at the University of Texas and is completing a book that grew from his dissertation, The Washington Correspondents and Government Information.

When Leo Rosten’s The Washington Correspondents was published, Edward Angly threw the author an acid salute, “At last,” Angly wrote, “someone has come along who takes the Washington correspondents as seriously as they take themselves.”

It was an intriguing line—and it may have performed the useful service of deflating some puffed-up correspondents—but it is hard to imagine worse timing. If Rosten’s book had been published ten years earlier, Angly might have been justified in the slur. Before the 1950’s, the correspondents were so nearly alone in considering their work important that its importance was diminished as a consequence. They were so little noticed that one suspects that the stereotype of the journalist of the 1920’s—perhaps he was a composite of Walter Winchell, Richard Harding Davis, and the local police reporter—ignored the Washington press corps altogether.

It should have been obvious to everyone by 1957, however, that the Depression and the New Deal had changed American journalism as well as American politics. For good or ill, the Washington correspondent was a man of the first importance. Rosten was simply the earliest of the social scientists to recognize the necessity for measuring political journalism.

“In a democracy,” Rosten wrote, “we depend on the press for a presentation of the facts upon which our political opinions are based and the issues around which our political controversies revolve, but we know nothing of the men, the women, the problems, the devices behind the dispatches and columns which begin with the portentous date-line ‘Washington, D.C.’” It seemed to Rosten that getting behind the dateline was a matter of the first significance. The fact that he succeeded may be suggested by the veteran correspondent who said, “Reading that book made us feel like we had been dissected.”

Now, twenty-five years after Rosten’s analysis, I am trying to update it. Inevitably, there are differences in the two studies. Newspapermen and wire-service reporters dominated the Washington press corps in the 1930’s and Rosten limited his investigations to them. Today, the radio, television, and magazine correspondents are quite as important, and they are included in my study. In part for this reason, and in part because of the growth of the press corps, my sample is larger than his, 278 to 127. (In both studies, the “official” lists of correspondents—all of which were misleading—were sifted to eliminate those who did not actually work as Washington correspondents. My figure for the total number of bona fide correspondents is 634, not the 1,500 usually cited.) In most significant respects, however the studies are similar. The same techniques—primarily interviews and questionnaires—were used in both, and many of the same questions were asked. And, perhaps most important, the motivation of both studies was the same: to discover the facts about an institution of American democracy.

Of all the changes in the Washington press corps during the past twenty-five years, none is more significant than a new sense of freedom from the prejudices of the home office. Rosten measured the degree of freedom to report objectively by including in his questionnaire a battery of statements that had been made by correspondents during interviews. One read: “My orders are to be objective, but I know how my paper wants stories played.” Slightly more than 60 per cent of the correspondents of the 1930’s replied “Yes” to this, indicating that they felt subtle pressure. Today, only 9.5 per cent reply “Yes” to the same statement.

This difference is so marked that one may immediately suspect that there was a misunderstanding or mistake. However, another statement that also tested freedom from home-office pressure drew a similar response. Rosten asked the correspondents whether this could be said of their work: “In my experience I’ve had stories played down, cut, or killed for ‘policy’ reasons.” Slightly more than 55 per cent of the correspondents of the 1930’s answered “Yes.” Today, only 7.3 per cent answer “Yes” to the same statement.

This is not necessarily a record in which the press can take complete pride. After all, nearly 10 per cent of the Washington correspondents will admit that they feel subtle pressure; more than 7 per cent will admit that they have been subject to direct retaliation. The change to these figures from 60 per cent and 55 per cent, however, is an improvement so startling that it demands explanation.

A veteran correspondent explains it by pointing out that the political issues are not nearly so clear cut today as they were in the 1930’s: “You’d have to have been around in the ’30s to understand the difference. The publishers didn’t just disagree with the New Deal. They hated it. And the reporters, who liked it, had to write as though they hated it, too.” According to this correspondent and others, the passing of the publisher-tyrants—the William Randolph Hearsts and the Robert R. McCormicks—has changed political journalism. “The day when a publisher would order his Washington bureau to beat a bill with news stories is just about gone,” he said.

This is not to say that the newspaper publishers and their correspondents now have the same political stance. In 1960, 57 percent of the daily newspapers reporting to the Editor & Publisher poll supported Nixon, and 16 percent supported Kennedy. In contrast, there are more than three times as many Democrats as there are Republicans among the Washington newspaper correspondents; slightly more than 32 percent are Democrats, and fewer than 10 percent are Republicans. About half of the newspaper correspondents today call themselves “Independents,” but it is notable that the newspaper correspondents, like the rest of the Washington press corps, are predominantly liberal. More than 55 percent of the correspondents for newspapers consider themselves liberals; 26.9 percent consider themselves conservatives.

There is very little difference politically between the newspaper correspondents and the correspondents for radio and television, wire services, and magazines. There are nearly four times as many Democrats as Republicans among the radio-te1evision correspondents, nearly four times as many Democrats as Republicans among the wire-service correspondents, and nearly twice as many Democrats as Republicans among the magazine correspondents. In the entire Washington press corps, liberals outnumber conservatives, 56.6 percent to 27.6 percent. (Interestingly, even though liberalism and conservatism have never been sharply defined—and the definitions that are used in Washington are subject to continuing debate—only 15.9 percent of the correspondents described themselves as “Middle Roaders” or refused to label themselves.)

It should be obvious from all this that most of the Washington correspondents believe that their superiors do not require slanted reporting. It is worth considering, however, whether this freedom is more apparent than real, as some social scientists believe. A study by Dr. Warren Breed that was published in 1955 is often cited as evidence that political correspondence is under control. Breed, a Tulane University sociologist who once worked as a newspaper reporter, analyzed six factors that may tend to produce general conformity to a newspaper’s policy among its staff. Most of the factors are subtle. For example, “in-groupness in the newsroom,” in Breed’s phrase, is that friendly, first-namish atmosphere in which staffers and executives often work together on a job they all like and respect: getting the news. Although Breed’s study was limited to newspaper newsrooms in the home office, the same atmosphere—and the same united effort of executives and staffers—can be observed in offices of mass media in Washington. Can part of the reduction in home office pressure be explained by the possibility that social controls have brought correspondents’ reports more in line with superiors’ policies?

This is certainly possible. It seems likely, however, that even the subtlest of these effects can be detected, especially by the correspondents today. For one of the most striking aspects of the Washington press corps is the level of formal education that most of the correspondents have reached. The Washington correspondent today was probably sitting in a sociology class not many years ago, and he may even have written a scholarly paper on social controls.

The rising level of education for all Americans leads one to expect that the Washington correspondents today would indeed have more formal education than those of the 1930’s. But the difference is greater than the changing times indicate. Even in this Age of Education, only one person in three of college age actually undertakes higher learning, and nearly half of those who enroll in College never earn a degree. Today, slightly more than 81 percent of the Washington correspondents have college degrees (51 percent in the 1930’s). More than 93 percent have attended college (79 percent in the 19303). More than 31 percent have done graduate work (12 percent in the 1930’s), and nearly 20 percent have earned graduate degrees (6 percent in the 1930’s).

The sociological composition of the Washington press corps has changed in other respects since the 1930’s, in ways that alter the folklore of American journalism. Folklore held that leading reporters usually come from the Midwest—especially from Indiana—and Rosten’s findings supported it. Indiana, with more than 10 percent of the correspondents of the 1930’s, and Illinois, with more than 9 percent, were the leading states of birth; the Midwest as a whole contributed more than 45 percent. Today, Indiana and Illinois are far down the list and the whole Midwest contributes only 30 percent of the correspondents. New York and Pennsylvania are now the leading states, and the Northeast is the leading region.

Another stereotype in the folklore of journalism, the impecunious reporter, also fails to hold up in Washington. It is perfectly true that Washington is a high-cost city, that few correspondents are likely to compile fortunes, and that many of them can complain justifiably that the man at the top of his profession should make more money. Nevertheless, by journalistic standards the Washington press corps is an affluent society. Only 2.6 percent of the Washington correspondents are paid less than $6,000 a year. More than 9 percent are paid more than $20,000. The median salary for all correspondents is $11,579, or $4,500 better than the national average for reporters, as determined in a 1960 study by the Associated Press Managing Editors, and more than double the median family income in the United States.

The radio-television correspondents are the best paid. Their median salary is $15,799, followed by the magazine correspondents ($13,299), the newspaper correspondents ($11,319), and the wire-service correspondents ($10,139).

Inflation makes highly suspect an exact comparison of the salaries today with those of the 1930’s. The fact that the salaries now are more than double those of the 1930’s is not altogether meaningful. In current dollars, the $5,400 median salary of 1937 would equal $11,055 today, or only slightly less than the current median.

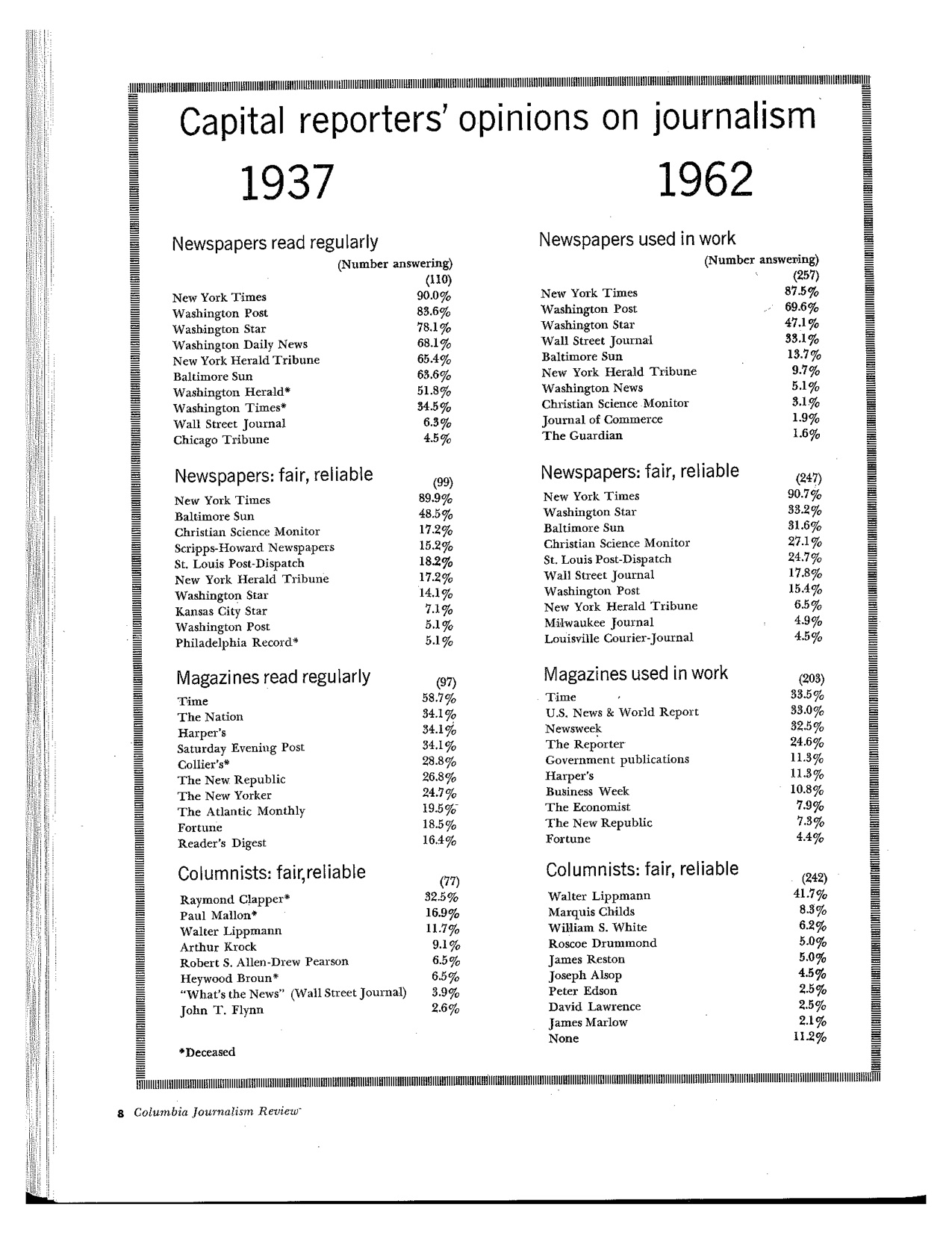

Only in recent years have social researchers begun to define elite groups in American society. Rosten did not try to define an elite among the correspondents of the 1930’s. He did, however, recognize the significance of the newspapers that the correspondents themselves read regularly and considered fairest and most reliable. Rosten also questioned the correspondents about the magazines they read regularly and the newspaper columnists they considered the fairest and most reliable.

On the theory that it might now be possible to define an elite within the corps of correspondents, I tried to determine which individuals, publications, and radio and television programs were most used and respected by the correspondents.

The first question ran: Which three newspapers (other than your own) do you rely upon most often in your work? lt is obvious that the Washington correspondents, like most people, will read the newspapers that are available in the cities where they live and work. This is especially true of Washington. The answers (see the table) show that correspondents read and rely heavily on two of the three local dailies, the Post and the Star.

The most striking aspect of this section of the study, however, is the continuing dominance of The New York Times. A total of 225 of the 273 correspondents listed it. The most obvious explanation of the reliance upon the Times is the attention that in gives to national and international affairs. Not only does Washington news dominate many of the pages of the Times, but the paper maintains a Washington bureau that is by far the largest of any single newspaper.

The list of twenty-one papers correspondents mentioned is a short one in view of the fact that more than 1,750 dailies are published in the United States. Since the nine leaders are all published in the eastern section of the country and almost all of them are morning papers, it can be argued that geography and time are important factors. This is certainly true. It is also true that many other metropolitan newspapers are flown to Washington and are available only a few hours after publication.

Another dimension of the elite character of some newspapers is shown in the answers to the second question: Which are the three fairest and most reliable newspapers? Again The New York Times was dominant, but more significant are the shifts of position in the responses to the two questions, with the Washington Star, the Baltimore Sun, the Christian Science Monitor, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch all moving up.

The differences in the two lists are not necessarily odd. Nor should the changes from one list to another suggest that the correspondents are relying on papers they do not trust. A correspondent may, for example, rely upon three newspapers and think well of their fairness and reliability, but decide that three others that he does not consider as useful rank ahead of them in judgments of fairness and reliability. It should nonetheless be obvious that a newspaper that has been used by a correspondent has had a full opportunity to prove to him that it should be given the highest marks for fairness and reliability.

It is not surprising that the three general news magazines—Time, U.S. News & World Report, and Newsweek rank at the top of the list of periodicals the correspondents rely upon in their work. They appear every week, and they are made up in large part of reports on national and international affairs. But it is surprising that even as at group the general news magazines do not dominate this list (see earlier table) as the Times dominates the newspaper list.

The reason for the comparatively small reliance on the news magazines may become clear in the judgments of their fairness and reliability. S0 many of the correspondents had mentioned during interviews that none of the news magazines could be trusted that it was decided to split these publications off from the other periodicals and try to determine which, if any, were considered trustworthy. The correspondents were asked to name the one news magazine they considered the fairest and most reliable.

It was a revealing exercise. Not only did 24.1 percent of the correspondents fail to list any news magazine, but 16.9 per cent wrote “None” and some of them decorated the margins of the questionnaire with such comments as “Are you kidding?” and “No such animal.” Newsweek, with 75 votes, led the list. It was followed by U.S. News & World Report, with 66. Time, which had been first on the “relied upon” list, received only nine votes for fairness and reliability. In addition, several correspondents listed publications that are not considered news magazines.

It should be mentioned that there is nothing necessarily strange about relying upon a news magazine without trusting it. A magazine, as well as a newspaper, can provide leads to stories.

The case of Time, however, offers a special insight into the Washington press corps. Time is widely read by the correspondents, it seems clear, because of its crisp cleverness. Two of the correspondents who wrote “None” in the space available for listing the fairest and most reliable news magazine added, “But Time’s the only one worth reading,” and “Time has the only literate writers.” One correspondent who dislikes Time intensely confessed that he could not bear to miss an issue. He paid for a subscription to it, then discovered that he could get each issue a day earlier by buying it at a newsstand. Unable to wait for his subscription copy, he began picking it up at the newsstand. “Then,” he said, “I cuss my way through it.”

Many of the correspondents also balked at judging the fairness and reliability of the magazines of politics and opinion. Thirty-four percent did not list a magazine in that category, and nearly l5 percent wrote “None.” Considering the number who wrote in comments like “These magazines deal in opinion” and “These aren’t supposed to be objective,” it is clear that many of the correspondents do not consider it possible for magazines of opinion to be fair and reliable. Of those who did offer judgments, however, a majority—ninety—listed The Reporter. The New Republic was second with nineteen. No other received more than seven.

A number of correspondents apparently also consider it impossible for any person who deals in opinion to be fair and reliable. Slightly more than 11 percent failed to list a newspaper columnist as “fairest and most reliable,” and nearly 10 percent wrote in “None.” It is nonetheless clear that Walter Lippmann stands highest among the columnists in judgments of fairness and reliability. He received 10 votes (see earlier table) and no other columnist was even close. There is a question, however, about the standing of James Reston of The New York Times, who may not have been given his due because of confusion. Reston, who tied with Roscoe Drummond for fourth place, also works as a reporter and as bureau chief.

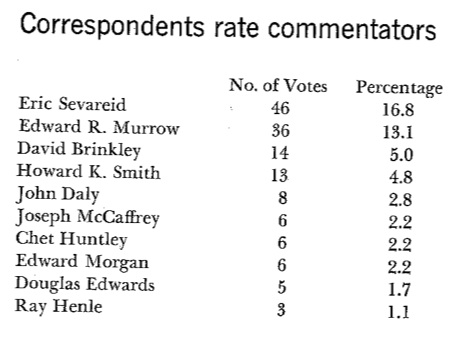

Like newspaper columnists, radio and television newscasters and commentators are considered by some of the correspondents not to be judged in terms of fairness and reliability. This became apparent in comments made during interviews, and it was borne out later in written responses. Nearly 25 percent of the correspondents listed no commentator as “fairest and most reliable;” nearly 17 percent wrote “None.”

It is nonetheless clear that a definable group of commentators stands high among the Washington correspondents. It is a group that CBS should ponder, for only one of the four, David Brinkley of NBC, is still working at the kind of reporting that gave him his standing among the correspondents. Eric Sevareid, of CBS, who was in first place with nearly 17 percent of the votes, is no longer reporting from Washington. Edward R. Murrow, who was second, left CBS shortly after the poll was taken. Brinkley was third. Then came Howard K. Smith, who quit CBS in 1961 in a policy dispute and is now with ABC. The ten leaders are listed in this chart.

Murrow, Daly, Huntley, and Edwards probably stood higher than the figures indicate. Although all of them report on politics, some of the correspondents undoubtedly failed to list them because they were not, at the time of the poll, working as Washington correspondents.

There are many important facets of life and work in the Washington press corps that cannot be analyzed statistically. Impressions gathered during three years of work and observation in Washington may help to round out the picture.

Accuracy? Some of the correspondents will admit that it is often sacrificed at the altar of speed. “I phone in the stuff from my beat,” a wire service reporter complains, “and it gets botched.” A newspaper correspondent: “My editor doesn’t realize how complicated Washington can be. He just wants copy.“ One of the leading columnists confesses, “I have to keep in mind always that if I don’t get my column in, the money won’t come in either.”

Depth reporting? At least one Washington correspondent customarily accosts his news sources with the cub reporter’s query: “Have you got any news for me today?” It is interesting, too, that when correspondents are asked to name the Washington reporters whose work is characterized by hard-digging investigation, the list is never very long. It is true, of course, that the Washington press corps is too large to permit any one correspondent to be able to evaluate the work of all the others. The recurring and six-name lists of reporters who persistently investigate in depth are revealing, nonetheless. They usually include, among others, Clark Mollenhoff of the Cowles publications, Vance Trimble of Scripps Howard, and Reston.

Perspective? Just as the home-city reporter writes about the local husband who decapitated his wife yesterday—not about the hundred thousand couples who lived happy lives—many of the Washington correspondents must focus on the flamboyant twenty-hour filibuster, not on the quietly effective ten-minute speech. Fixed ideas of what constitutes Washington news work against coverage in depth.

And yet, with all of the shortcomings, the dominant impression is one of advance over 1937. Accuracy is highly prized; the inaccurate report is the exception. Even those correspondents who are hard-pressed for time occasionally report in depth. Reading the newspapers and magazines of the 1930’s against those published today leaves one with a distinct feeling that analysis and interpretation of meaningful events are now providing more perspective on government.

Today, the thrust of the Washington press corps is not expressed by the correspondent whose greatest pride is that he once covered the police beat but by the correspondent who does not hesitate to use that sticky word “professionalism.” It is probably significant that one almost never hears journalism referred to as a “game.” Instead—at least among the younger correspondents—it is often “this profession,” or “my profession.” The correspondent who will say, as one did recently to a student group, “Hell, 1et’s be honest, we’re here to have as much fun as we can,” seems to be disappearing.

One striking evidence of seriousness and purpose in the Washington press corps is reflected in Walter Lippmann’s changing opinion. He sees a profound improvement in political journalism. The difference is so great that he no longer laments, as he did in the 1920’s, that journalism is only a “refuge for the vaguely talented.”

Archives:

Archives: