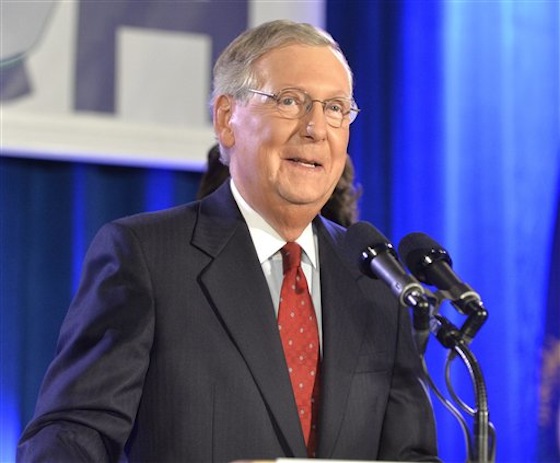

Majority leader Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) celebrates his landslide victory Tuesday night. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)

Majority leader Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) celebrates his landslide victory Tuesday night. (AP Photo/Timothy D. Easley)

The major political storyline emerging in the aftermath of Tuesday’s elections wasn’t that Republicans took control of the Senate or painted additional governors’ mansions red. It was how handily they did so. Projected toss-ups became easy GOP wins, and a few races in which Democrats seemed to hold slight leads eventually went Republican. The Washington Post described the performance as “A Republican wave” at the top of A1 on Wednesday morning. The Houston Chronicle went one step further with “Red tidal wave for GOP,” while the Kansas City Star conjured images of a political bloodbath: “Red Tuesday.”

Forecasters had long predicted that the GOP would command the Senate come 2015. But public opinion polls suggested that key Senate and gubernatorial races would be tight, with many projected margins of victory inside the surveys’ margins of error. Even Nate Silver, the forecasting wunderkind and editor of FiveThirtyEight.com, expected a squeaker in the upper chamber of Congress.

The political press generally took pre-election polling data at face value, both for the nationwide Senate battle and in individual races. On Monday, a Politico piece explained that “it could be days, weeks or even months before the Senate is awarded to one party or the other.” The next day, an election preview by New York Times campaign guru Nate Cohn predicted “one of the most dramatic election nights in a long time.” A Nov. 3 msnbc.com story bullishly described how the Kansas Senate race “could throw a wrench” into Republican efforts to control the upper chamber (incumbent Sen. Pat Roberts eventually won by more than 10 points). And The Post’s Chris Cillizza declared on Oct. 21, “Kentucky isn’t a blowout today, and it won’t be two weeks from today, either.” (GOP Sen. Mitch McConnell ended up winning by more than 15 points.)

The media’s expectation of closer races — an expectation fueled largely by a reliance on polling data — spanned the country. When the dust settled on Wednesday, however, the danger of taking the polls as gospel became all too apparent.

“This year was one of the biggest polling misses that we’ve seen in the past 10 or 15 years,” said Drew Linzer, the California statistician behind Daily Kos’ election forecasting model. “This is an issue with the polling, not the aggregation.”

It remains unclear why surveys underestimated Republican support this year. As Mark Blumenthal and Ariel Edwards-Levy write at the Huffington Post, pollsters “likely missed the true composition of the electorate, probably including too many Democratic-leaning voters who chose to stay home.” Internet polling is still nascent. And telephone survey response rates dropped from 36 percent in 1997 to 9 percent in 2012, according to a study by the Pew Research Center.

“When you have fewer respondents, you have to make bigger inferences,” said Joshua Tucker, a New York University professor who contributes to The Post’s Monkey Cage blog. “That weighting becomes more important.”

Polling experts frequently qualify their analyses, though those qualifiers rarely make it into mainstream political coverage. Predicting elections can be dangerous territory for journalists, and CJR recently wrote about how poll stories show only part of the picture. News organizations tend to cover self-commissioned surveys in a vacuum, despite widely available polling averages and forecasting models. Tuesday’s election results suggest those data deserve a high level of scrutiny as well to add context and caveats to campaign reporting. The science of polling remains extremely complex, and evaluating races requires far more than a simple glance at the latest numbers.

Survey biases — results inaccurately favoring one party or the other — aren’t uncommon. But their magnitude this year caught political reporters off-guard, especially given the high volume of polling in some states. The average Senate poll conducted in the three weeks before Election Day skewed toward Democrats by 4 percentage points, according to an analysis by Silver. In hotly contested Senate races in Iowa and Arkansas, for example, Republicans outperformed poll averages by 7 and 12 percentage points, respectively. Gubernatorial races saw similar pro-Democratic biases in their pre-election surveys.

As Fox News’ Howard Kurtz aptly points out, political observers need look no further than the Virginia Senate race and Maryland gubernatorial contest — both just outside the Beltway — to see the failure of reporters to produce more comprehensive coverage. The heavily favored Democrat Mark Warner eked out a victory in Virginia, while apparent underdog Larry Hogan, a Republican, won decisively in Maryland. But coverage by The Washington Post, for example, was colored by poll results suggesting easy Democratic victories.

“A hometown paper like The Post should have picked up the dramatic swings in these races from its own door-knocking and pulse-taking and covered them as daily front-page dramas,” Kurtz writes.

That sort of shoe-leather reporting is difficult and expensive, especially so for outlets covering races across the country. It’s simply easier for journalists to rely on survey data, especially when it’s all available in one place. Aggregation reduces variance, however, not bias. While the latter clearly affects both the tenor and intensity of news coverage, it remains difficult to counter when surveys are being conducted.

Finding the right formula is no small task for pollsters. Their data is an extremely useful reporting tool, to be sure, but not the only one. Journalists shouldn’t be lulled into complacency by the proliferation of forecasting models and aggregators, such as the Real Clear Politics polling average. The elections during which such tools came to mainstream prominence, 2008 and 2010, saw much more accurate polling averages nationwide. “The 2004 race swung a few times over the course of the campaign,” Sam Wang, founder of the Princeton Election Consortium, wrote in an email. “That would have been a good lesson for people in the uncertainties that were present in this year’s Senate campaign.”

Wang channeled those uncertainties in a New Yorker piece on Tuesday, concluding, “In a time when polling analysts have proliferated with alarming speed, perhaps the only thing we can all bank on is uncertainty.”

Archives:

Archives: