The word of the National Football League commissioner is not law. But the opening line of a 2,300-word piece in the Buffalo News last month might have fooled casual readers: “The question has been on the minds of every Buffalo Bills fan ever since National Football League Commissioner Roger Goodell said the team needs a new stadium: Where should it be?”

Good question — or at least it would be if a new stadium was a certainty or official plans were looming. The Bills, however, are essentially locked into playing at their current Ralph Wilson Stadium through at least 2019. Though the team is on the auction block, it’s unclear who will own the franchise next year, let alone if he or she will want to build new digs. Even then, New York state and local politicians have said they’re reluctant to pony up the hundreds of millions in taxpayer dollars usually required to construct such lavish venues.

The Ralph The Buffalo Bills play the Pittsburgh Steelers at Ralph Wilson Stadium during a 2012 preseason game in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/David Duprey)

The News isn’t the only media outlet in western New York that has run stories implicitly — or even explicitly — supporting the idea of a new stadium. Indeed, Buffalo’s alternative weekly unveiled its own plan for a downtown venue in a cover story this month. Local TV and radio reports have focused on proposed building sites, asked readers to weigh in on them, and trumpeted the purported economic benefits. National and sports media, meanwhile, have echoed Goodell’s claim that the Bills need a new home to remain economically viable. That’s not to say all coverage of the issue has toed the NFL line. But a new stadium is neither imminent nor inevitable, facts that the balance of reporting haven’t reflected.

The question of financing such venues is, at its core, a political one: Should the public subsidize a lucrative local business to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars? Media scholars and economists have long criticized news organizations for tacitly endorsing these ideas. Sports coverage is among the greatest draws of local media, and the deluge of stadium speculation puts political pressure on local officials to deliver. Reporters have a history of biting on economic impact studies that overestimate spinoff benefits. And the undercurrent throughout the coverage is the unspoken threat of becoming a minor-league city if a major-league team skips town.

“America has a culture that tends to want to be behind a winner,” said Robert Trumpbour, a communications professor at Penn State Altoona and author of The New Cathedrals: Politics and Media in the History of Stadium Construction. “The media can be part of that dynamic as well. They come together to create a situation in which there’s a lot of support for stadium building, even if the public doesn’t want to pay for that.”

The situation that’s developing in Buffalo is familiar to many major American cities: A professional sports franchise owner, threatening to take his or her business elsewhere, garners public funds, sweetheart tax deals, or cheap property to help construct a spanking new sports complex. These magnates — and some of the politicians that enable them — market such investments as engines of development, often commissioning rosy economic reports to prove their point.

Journalists have often taken such numbers at face value despite stadiums’ dubious economic history, said Victor Matheson, a Holy Cross professor who studies sports economics. It’s especially evident in day-one stories, as reporters work under time constraints that make nuanced analyses difficult. In such pieces on July 20 detailing a planned downtown arena for the Detroit Red Wings, for example, both the Detroit Free Press and Crain’s Detroit Business cited projections from team ownership of $1.8 billion in resulting activity. The latter, which has in the past reported critically on stadium payoffs, at least acknowledged in its story that the numbers are sometimes off the mark.* But it had just over a day to dissect the embargoed information before going to print.

“For us to process and analyze the sheer amount of information in 24 hours would be impossible,” said Bill Shea, who covers the business of sports at Crain’s. “The balance of our reporting has been different.”

Detroit’s ABC affiliate, WXYZ, both repeated the rosy economic numbers and neglected to remind viewers that the $450-million arena will be built primarily on the public’s dime.

It’s unclear if the yet-to-be-built stadium will bring such prosperity to the struggling city. But independent economic analyses of past projects, which overwhelmingly conclude that sports venues are poor public investments, deserve at least a cursory mention. As Matheson told CJR, “We generally don’t find those [economic] bumps. And when we do find those bumps, they tend to be about one-tenth to one-fifth of what was claimed.”

The Los Angeles Times and Orange County Register last year displayed similarly less-than-critical coverage of the public cost and potential economic windfall of a longterm lease agreement with the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. Though the Register eventually published a more comprehensive analysis of the plan, it came two months after the Anaheim City Council had agreed to the deal.

But as more and more cities get burned, and academic literature on the reality of such deals becomes more widely available, the cheerlead-first, ask-questions-later mentality is gradually giving way to more skeptical views. At the same time, though, professional sports leagues grow increasingly adept at marketing their wares. And some journalists still struggle at the awkward intersection of sports, business, and political narratives, said Neil deMause, a New York-based reporter who specializes in stadium construction (and who, full disclosure, used to do some contract work for CJR).

“You might end up with sportswriters covering this, whose eyes glaze over when they see an economic-impact report,” said deMause, who co-authored a book, Field of Schemes, on the topic. “Or you have news people handling it, who might be able to handle the economic aspects, but they can easily get distracted by the sports aspect of this.”

He added, “When you have to fight against the fact that nobody has this issue as their beat, no one has the time. It’s easy to cover it in a very surfacey way.”

What’s more, said Daniel Mason, a University of Alberta professor who studies sports coverage, media are beneficiaries of pro-growth development policies and can be inherently biased toward new stadiums. In Cleveland, Mason said, where public referenda nixed plans in 1984 for a football stadium but supported a 1990 proposal for new baseball and basketball venues, both news stories and commentary from local papers leaned toward subsidized projects.

“Local media are stakeholders in the growth machine within a city, so they benefit from the presence of a team,” Mason said. “If a franchise moves, the first person to lose his job is the sports reporter.”

Buffalo is still in the early stages of the new-stadium discussion. And media coverage has fixated on potential sites, generally avoiding questions of whether a new stadium is necessary or how local and state governments intend to pay for it. To be fair, New York State has commissioned a study to evaluate plans to either construct a new facility or renovate the Bills’ existing stadium, which already received a $226-million commitment from Albany last year for renovations and operating subsidies. But there’s no release date for the report in sight — it’s an election year, after all.

News editor Mike Connelly insists the coverage isn’t getting ahead of itself. And his newspaper has in fact sprinkled in more critical stories, including a deep dive Monday detailing how the Kansas City Chiefs refurbished their existing venue. In late July, the paper also evaluated sports owners’ bargaining power and asked an important question: Is a new stadium worth it?

“It’s a story with a lot of different facets, and we want to report them all,” Connelly said in a phone interview. “For a story that is of such incredible interest to our community, my attitude is that you go aggressively at all those different aspects. If you do the coverage correctly, everyone will get smarter about the issue.”

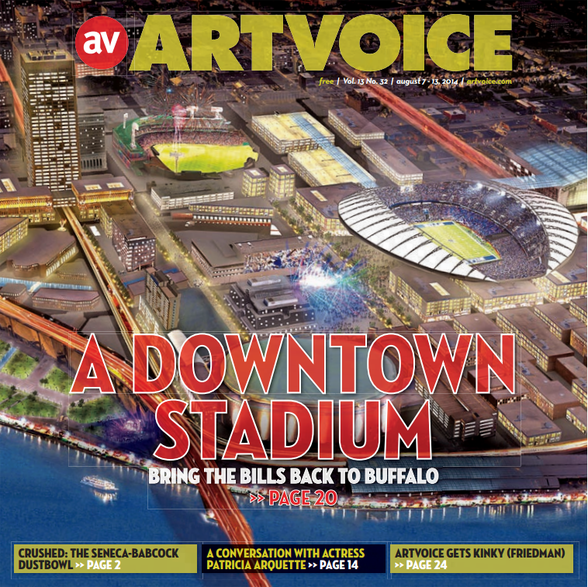

Artvoice, Buffalo’s alternative weekly, has taken a more activist approach, publishing a 2,700-word cover story with its own vision for a downtown stadium. “We wanted to throw something out there and head off a lot of bad ideas before they get developed,” editor Jamie Moses said. “If there’s a choice to make, the city has traditionally made the worst choice. It’s such a habit with them.”

The weekly teamed up with an urban planner to devise its proposal for a new stadium district, a monthlong process. In a phone interview last week, Moses acknowledged that such megaprojects don’t usually pan out, though he believes Artvoice’s blueprint will have better fortunes. While the anticipated price tag — $1.5 billion — doesn’t appear till near the end of the piece, Moses said, “We didn’t care about the cost. We know it’s going to cost a lot. The plan was to put the ideas out there. If people buy the ideas, they’ll find the money.” The feature has remained on the website’s “What’s Popular” list for nearly three weeks.

The weekly teamed up with an urban planner to devise its proposal for a new stadium district, a monthlong process. In a phone interview last week, Moses acknowledged that such megaprojects don’t usually pan out, though he believes Artvoice’s blueprint will have better fortunes. While the anticipated price tag — $1.5 billion — doesn’t appear till near the end of the piece, Moses said, “We didn’t care about the cost. We know it’s going to cost a lot. The plan was to put the ideas out there. If people buy the ideas, they’ll find the money.” The feature has remained on the website’s “What’s Popular” list for nearly three weeks.

Whereas the News has covered all angles of the issue, premature or not, and Artvoice openly advocates for a specific outcome, Buffalo Business First hasn’t touched new-stadium speculation. And it’s done so despite Bills stories generally being “click magnets” online, editor Jeff Wright said.

“We want to see what the ownership is going to be before we really throw ourselves into the stadium issue,” he said.

But history is paramount, especially in cities like Buffalo, a place that has watched residents and investment migrate elsewhere over the past half century. The Bills are not only a gridiron spectacle on fall Sundays, but also a prominent local business and an integral part of the area’s identity. The assumed possibility of the team’s departure thus poses even more complex questions to reporters, who must evaluate both tangible and intangible benefits of the proud franchise. The challenge is to ensure that reporting on one doesn’t affect reporting on the other.

“There are only 32 NFL teams, and that’s a pretty elite club to be in,” Wright said. “When you’re not in it, you don’t feel as good as you do when you’re in it.”

UPDATE: Bill Shea, a reporter at Crain’s Detroit Business, argues that stadium plans — on which he wrote a day-one story mentioned above — and debates on their economic impact are separate topics suited for separate stories. “The thrust of this piece was not about the economics of the stadium,” Shea told CJR. “We have pointed out for years that these economic impact studies are usually bunk. It’s a fact that this will change downtown. The economic impact is a different issue.”

Archives:

Archives: