Early one morning in El Salvador’s provincial capital of San Francisco Gotera this past March, the crack of a gunshot—or something that sounded like one—echoed over the deserted cobblestone streets. Harry Mattison, the former Time magazine photographer who worked here during the civil war, blanched and stopped dead in his tracks.

“All of a sudden, you hear a bang and time collapses,” he said.

These days the entire country, the smallest in Central America, may be experiencing a similar sense of the past stalking the present. Only three days earlier, Mattison had been in San Salvador’s Sheraton Hotel for the victory speech of Mauricio Funes. The presidential candidate of the former guerrilla forces, the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, or FMLN, which has been a political party since the war’s end in 1992, Funes, forty-nine, had just ended the monopoly on power held by the right for much of the country’s history. Hundreds of small red flags with a white star, an icon of the war, fluttered through the audience.

Nearly three decades have passed since the start of El Salvador’s twelve-year civil war, a vicious conflict that killed 75,000 people, but with the ascension to power of the FMLN, that past has risen once more to the surface. Indeed, the civil war was a constant undercurrent during the presidential campaign between Rodrigo Ávila of the Nationalist Republican Alliance, or ARENA party (founded by Roberto D’Aubuisson, the organizer of the death squads), and the FMLN’s Funes, a former journalist whose older brother fought with the leftists and was killed during the conflict.

The war in El Salvador was the last great showdown of the cold war. Concerned about a domino effect in Central America at a time when Nicaragua had already fallen to the Sandinistas, the U.S. government in the 1980s poured money into the coffers of the right-wing junta despite its association with the paramilitary death squads that terrorized the civilian population with a campaign of kidnapping and murder.

For journalists like Mattison, the war—during which it was common to find bodies with their hands tied behind their backs strewn along the highway stretching from the airport to the capital—was especially brutal. “I think it was one of the worst stories one could cover,” said Bernard Diederich, Time’s former bureau chief in the region. “You’d go out in the morning and do the body count, before or after breakfast, but better before… It was mad.”

The gallery of photographs on this site represents the work of six American and French photojournalists who were present during the earliest days of the conflict. For this generation of photographers, El Salvador would prove the most lethal story of its time—according to the Journalists Memorial in Washington, D.C., even more deadly than Vietnam.

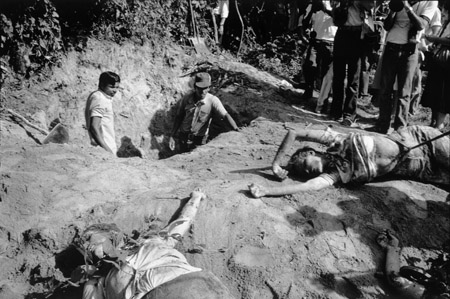

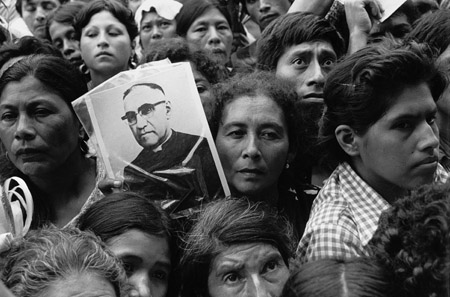

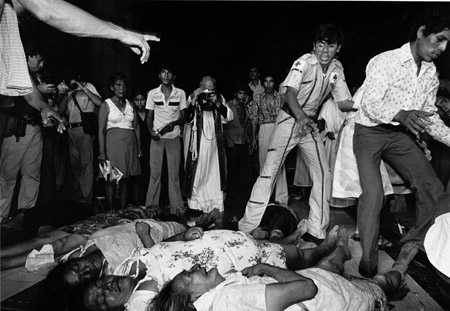

The killing kicked into high gear in 1980. The Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero, was assassinated during a Mass on March 24. His followers, who had gathered at Cathedral Square, were then gunned down, with dozens killed. Perhaps even more outrageous to the American public was the rape and murder of four American nuns on December 2, 1980. Photographs of the unearthing of the bodies, including those taken by Susan Meiselas (some of whose pictures are presented here), provoked such an outcry that then-President Jimmy Carter ordered a freeze on funding to the junta.

Shortly after, in the face of the impending inauguration of Ronald Reagan, whose policies on Central America were known to be hawkish, on January 10, 1981, the FMLN launched its “Final Offensive,” intended to rouse the population to topple the government. Though ultimately doomed, the offensive initially made great strides, particularly in the northeast province of Morazan, where guerrillas overran the provincial capital of San Francisco Gotera.

Two days after the start of the operation, Meiselas, John Hoagland, a photographer for Newsweek, and Ian Mates, a South African cameraman, set out in a car heading north from San Salvador. While riding on a dirt road, they hit a land mine. All three were injured, Mates with a serious head wound. Hoagland ran for help. But by the time the three managed to return to the capital, it was too late to save Mates.

The following day, Meiselas and Hoagland were visited in the hospital by some of their colleagues, including Mattison and Olivier Rebbot, a thirty-one-year-old French freelance photographer working for Newsweek. In the face of successes by the FMLN, President Carter reinstated funding for the government on January 14. Undeterred by the danger, in the early morning of the following day, Mattison and Rebbot, along with photographers Murry Sill from the Miami Herald and French shooters Alain Keler and Benoit Gysembergh, headed north from San Salvador.

By the time the photographers reached San Francisco Gotera, government forces had retaken the town and waved them in. The five set out on foot up the road. The sun was blazing, and a few took pictures of the body of a dead guerrilla fighter lying in a ditch being eaten by a dog.

Gunfire erupted as leftist fighters began shooting from the hillside. Rebbot crouched beside a low stone wall, but was struck by a high-powered bullet that tore through his flak jacket and passed through his chest. He fell backward into the road.

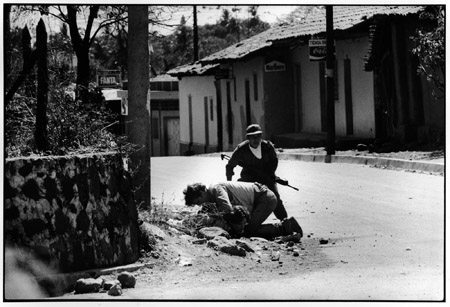

Mattison, seeing Rebbot fall, ran to him and laid on top of Rebbot’s body, trying to shield him from further gunshots. Pinned down by the gunfire, Sill, Keler, and Gysembergh, who witnessed the event, all photographed it, and on their contact sheets the horrific scene unfolds in timeless black and white: Mattison atop his colleague, turning him over to assess his wound, then helping to drag him into the back of an ambulance.

The next day, Mattison accompanied Rebbot on a chartered flight to a hospital in Miami. Mattison then returned to work in El Salvador. Rebbot died three weeks later. He was not the first or the last journalist to die in El Salvador—some were deliberately targeted. Of the eight photojournalists mentioned in this story, three were killed (John Hoagland, who was on a government hit list, was gunned down in El Salvador in 1984).

Nearly all the journalists who covered the conflict would insist that the loss of their colleagues was insignificant compared to the losses suffered by the Salvadoran population, yet his failure to save Rebbot continues to haunt Mattison, who this year returned to the country for the first time since being expelled by the government. “I told him he’d live. I lied.”

The new president, Mauricio Funes, wants to maintain warm ties with the U.S. and has said that he will not overturn a law providing amnesty for war crimes committed during the conflict. In the dangerous pas de deux between forgiving and forgetting, however, he insists that “the state has to recognize that it committed human rights violations.”

The historic change in El Salvador’s government, which successive U.S. administrations fought so hard to prevent, offers an opportune moment to remember those who created the images that shaped our collective memory. Camped out at the Camino Real Hotel in San Salvador, this small and dedicated community of journalists knew and protected one another, and courageously took on the dangerous task of making the photographs that sometimes embarrassed both the Salvadoran junta and the U.S. government that supported it.

A victim of civil war violence, San Salvador, January 1981 (Credit: Olivier Rebbot/Contact Press Images)

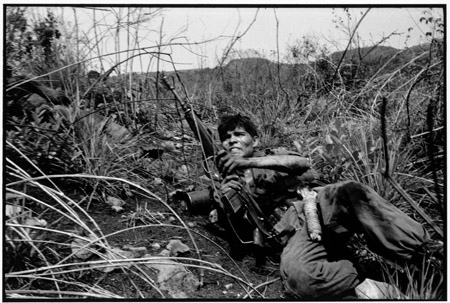

In one of Olivier Rebbot’s last pictures, a soldier reacts to gunfire during a battle between government forces and leftist guerrillas, San Francisco Gotera, El Salvador, January 15, 1981 (Credit: Olivier Rebbot/Contact Press Images)

Susan Meiselas

EL SALVADOR. Santiago Nonualco. 1980. Unearthing of three assassinated American nuns and a layworker from unmarked grave. (Credit: Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos)

EL SALVADOR. Cabanas. 1983. Soldiers under fire. (Credit: Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos)

EL SALVADOR. 1980. Soldiers search bus passengers along the Northern Highway. (Credit: Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos)

Harry Mattison

Mourners in the plaza of Metropolitan Cathedral during the funeral for assassinated Archbishop Oscar Romero, San Salvador, March 30, 1980. (Credit: Harry Mattison)

Interior of the Metropolitan Cathedral after the killing of mourners at Archbishop Romero’s funeral, San Salvador, March 30. 1980. (Credit: Harry Mattison)

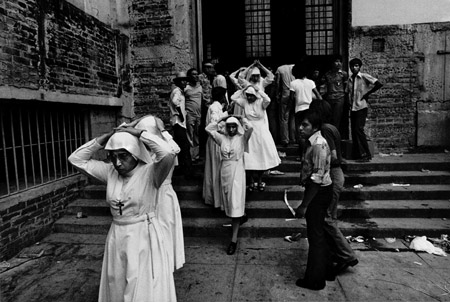

Nuns being forced out of the Metropolitan Cathedral, San Salvador, March 30, 1980. (Credit: Harry Mattison)

Benoit Gysembergh

Harry Mattison comes to the aid of Olivier Rebbot, mortally wounded during a battle between government forces and leftist guerrillas, San Francisco Gotera, El Salvador, January 15, 1981. (Credit: Benoit Gysembergh)

Murry Sill

Olivier Rebbot, moments before he is fatally wounded by gunfire, San Francisco Gotera, El Salvador, January 15, 1981 (Credit: Murry Sill)

From Sill: “This young orphan lived in the streets of Soyapongo, El Salvador. According to older children, his parents had recently been killed by soldiers. Shortly after making this picture, I watched a group of soldiers stop their truck, get out, shoot a man then continue on their way.” (Credit: Murry Sill)

Alain Keler

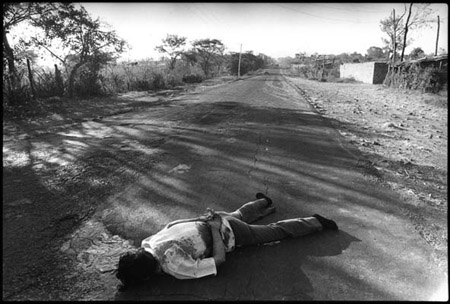

A victim of the right-wing death squads lies in the middle of a highway. January 17, 1981 (Credit: © Alain Keler / Corbis Sygma)

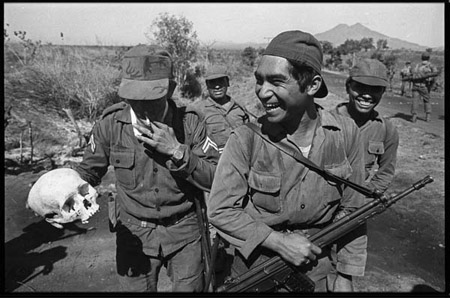

Government soldiers on a coastal road. February 8, 1982 (Credit: © Alain Keler / Corbis Sygma)

Archives:

Archives: