If clicks drove coverage at The Times-Picayune in New Orleans —a more realistic prospect than it’s ever been—what kind of publication would we get? We can look at past traffic and get a rough answer: In a doomsday scenario, we would read only about sex, sports, crime, and more crime. The most clicked on stories in the month of June, for instance, included the following headlines: Child among five shot (#1 most viewed); Gretna attorney accused of masturbating in law firm associate’s office (#4); Tattoos help Mississippi deputies identify dismembered remains of Jaren Lockhart (#7); and The deadline to sign Drew Brees to a long-term deal is looming (#13).

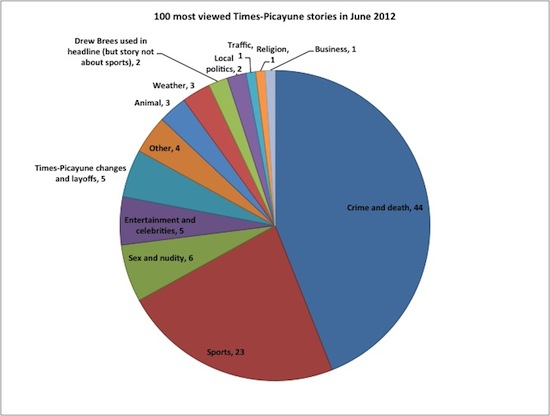

The 100 most popular stories that month included no coverage of education, health, immigration, or housing. Less than 10 percent of the stories were even tangentially related to social or public policy. Only two addressed a serious political debate (and one of the two probably made the list simply because Drew Brees was mentioned in the headline). But the stories documented murder, mayhem, and mischief in abundance. As a chronicle of human cruelty and misfortune, the list was nothing short of sublime.

It’s not unsurprising, of course, that sensational and tawdry headlines, pictures, and stories attract eyeballs, both online and in print. The tabloid formula goes back decades, and modern outlets like The National Enquirer and Gawker have used it to their advantage for years. More traditional, community-oriented newspapers have historically taken a different, and more paternalistic, approach. They have always covered their fair share of sports, crime, and fluff, but they include vegetables in addition to dessert, aiming for the balanced meal.

NOLA Media Group, the company that will run both the Times-Picayune (once it converts to publishing three times a week) and the expanded nola.com website, has not said explicitly how, or whether, clicks will drive coverage. And the Times-Picayune leadership has said in meetings with reporters that they will not abandon entirely subjects that fail to attract many eyeballs online (although the layoffs decimated the ranks of the news reporters and left the sports and entertainment departments comparatively intact).

But company officials have made it clear a major goal of the revamped website will be maximizing pageviews: The site, we are told, will emphasize sports and entertainment coverage as well as perpetual churn of stories on nola.com’s homepage. Based on new job descriptions, many reporters in the editorial department (renamed “Content”) will post several updates a day on the homepage’s breaking news blog (renamed “The River”), where some will be read by an editor (renamed “Quality Assurance Producer”) after the fact.

In the not-too-distant future, reporters’ bonuses, and possibly even part of their compensation, will likely be tied to a not-year-defined set of Internet metrics. A precedent established at the MLive Media Group in Michigan, the first Advance Publications property to go digital, offers a telling clue: In Michigan, reporters say their bonuses are based on the number of stories they post, the number of times they engage with readers through the comment stream, and the number of pageviews their stories receive. Pageview and posting goals are developed individually and do reflect reporters’ starting point and beat. Both the Detroit Lions reporter and the schools reporter might strive to increase average story clicks by 25 percent, for instance. For the sportswriter, however, that translates into thousands more clicks per story than the education writer, whose articles will never attract as many eyeballs. And reporters say they have been told to continue to prioritize quality journalism and not simply chase clicks. But whenever the well-trafficked Drudge Report picks up a story, there’s elation in the newsroom (renamed “the Hub”).

The most viewed stories on nola.com, by topic, during the month of June. The data for this graphic and story were compiled in late June and early July. The results can change over time.

I have covered education for the last 13 years—three of them as a New Orleans schools beat writer for the Times-Picayune. During the last two years, I worked limited hours at the newspaper, editing on Saturdays and contributing occasional stories on education, a position that will end when the transition to digital occurs in the fall. While I do not plan to apply for a new position at the NOLA Media Group, I think often about what the changes could mean for the newspaper, the community, and my talented colleagues, particularly if pageviews drive coverage and compensation to a significant extent. For this reason, I collaborated with Cathy Hughes, an online editor at the Times-Picayune, to compile and analyze data showing which stories receive the most pageviews. The data left me with two big fears.

First, if existing click patterns drove coverage, the newspaper would write almost exclusively about the dead, the dying, and the overpaid. New Orleanians would read about two tiny, polarized slivers of society: The fantastically wealthy and privileged sports stars and celebrities (particularly the white celebrities); and the fantastically violent criminals and their unfortunate victims (particularly the white victims). As they did in June, the big sports and crime stories almost always generate the most clicks. Stories about education, healthcare, and the overwhelmingly majority of poor people who do not kill anyone receive comparatively few.

Exceptions will always exist. In June, for instance, the opening salvo of a deeply reported May series on Louisiana’s prisons, by (departing) Times-Picayune staff member Cindy Chang, continued to be one of nola.com’s most visited stories. And an elegant feature on a former Louisiana pastor’s conversion to “non-belief,” written by (laid off) religion writer Bruce Nolan, also made the list. Bloggers went wild over that one. (Indeed, if you do not write about crime or sports, one of the best ways to inflate clicks is to get the most extreme bloggers or tweeters in your field to post links.)

The most-viewed stories included little about the universal experiences of living, working, loving, voting, getting sick, going to school, and worshiping (or not worshiping), in a complicated—and frequently unjust—world. They documented societal extremes. If such coverage were prioritized, we would be left with two visions of New Orleans: one focused almost entirely on the city’s theme park qualities and the other on its horrific violence; one describing a culture of escapism and the other a culture of degradation; one obsessed with wealth and the other with suffering. We would know all there is to know about Drew Brees’s contract and the most sensational of the city’s homicides, but much less about everything else.

My second overarching concern with clicks-driven local journalism—which I hope, like the first, will remain hypothetical—is the impact it could have on specific beats. Even if the new organization maintains its commitment to a subject like education, as company leaders have pledged to do, a metrics driven approach could still prove disastrous.

Articles about suburban and private schools, as well as higher education, receive more clicks on average than those about the New Orleans public schools, home to one of the country’s most controversial and consequential efforts to remake an urban school system. In June, for instance, seven of nola.com’s top 10 viewed education stories were about suburban Jefferson Parish. (Rounding out the top 10 were a piece about a leadership change at a private school; one on new research out of Tulane University; and a third on the discovery of 20,000-year-old pottery in a Chinese cave.)

If clicks drove coverage on the education beat, not only would reporters write less about the city schools, they would focus disproportionately on what I would describe as micro-feuds—intense, bitter, and divisive issues that are relevant only to a small fraction of society. The three most clicked-on education stories of the last five years, for instance, documented controversy over the firing of a principal at a local Catholic school; the closure of a Lutheran school in a New Orleans suburb; and the departure of the president at yet another private school. To the students, parents, staff, and alumni of these schools, coverage of the changes was deeply important. But to more than 90 percent of New Orleanians, it was close to meaningless.

At first it seems counter-intuitive that the most universally relevant articles tend to be the least popular. But it makes sense that we gravitate to journalism that taps into our deepest fears and longings, as well as articles that affect our lives in very obvious ways. They are stories that excite our emotions because of their exotic nature or personal relevance. They are not, however, stories that encourage us to see and understand the more subtle and important ways in which policy connects to our daily lives, and the ways in which we all connect to each other. Fostering that understanding is, in my mind, the most exalted, worthwhile function a community newspaper can serve.

Archives:

Archives: