NEW HAMPSHIRE — As tonight’s presidential debate approaches, the chattering classes are pondering whether it will change the dynamics of the campaign, which currently favor President Obama over Mitt Romney.

The odds are that it will not—most debates are non-events, at least in terms of electoral impact; political science research suggests that they rarely cause a significant change in the polls. To the extent that debates do matter for the horse race, however, the most important mechanism seems to be not the content of the debate itself but the interpretation adopted in subsequent media coverage. Given these stakes, it’s vital that journalists be wary about coalescing too readily on a common narrative—and that they be especially skeptical of post-debate spin.

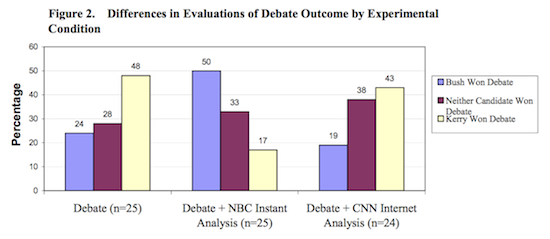

Some evidence that post-debate coverage matters comes from an experiment conducted by University of Arizona political scientist Kim Fridkin and her colleagues in 2004. The researchers found that exposure to NBC News’s instant analysis of the third debate between President George W. Bush and John Kerry, which was highly negative toward Kerry, had dramatic effects on viewers’ perceptions of who won:

In some cases, these effects may fade away as people forget the spin they’ve heard or read. In others, however, a debate narrative can take hold that may damage a candidate. Georgetown’s Erik Voeten and the late George Washington Professor Lee Sigelman found that perceptions of Al Gore as “too negative” relative to George W. Bush increased after the first presidential debate in 2000—presumably because of the “sighing” narrative that took hold among the press.*

The 2000 case in particular offers a cautionary tale, because it shows how the media can focus on a particular moment or narrative. In that case, Gore’s supposed pattern of sighs didn’t prevent him from winning the instant polls conducted among viewers of the debate (to be fair, these polls have methodological flaws). And only one Gore sigh was mentioned in the initial Associated Press wire story on the debate—in the sixteenth paragraph at that. But after the sighs were discussed in post-debate coverage on Fox and MSNBC—presumably prodded along with suggestions by Bush surrogates and allies—they came to be featured much more extensively in post-debate coverage and may have subsequently damaged Gore’s image.

For example, the next day’s Boston Globe featured Gore’s sighs in an A1 news report (“he frequently looked askance during Bush’s attack, sometimes shaking his head and sighing”), an A1 news analysis (“on occasion, a very audible geyser of exasperated sighs”), an A25 news story on watching the debate with a small group of voters in Missouri (“Some voters in Webster Groves have a tip for Vice President Al Gore: Lose the sigh.”), and four separate opinion pieces.

It’s possible, of course, that all of these journalists independently concluded that Gore’s sighs were one of the most important events at the debate (though if that’s the case, it’s likely because the sighs fit neatly into a characterization of Gore that the media had constructed over the preceding months). But it’s more likely that the media converged on that narrative as reporters digested interpretations of the event that were being offered to them in real time and immediately after the fact—a process that can happen more seamlessly than ever in the Twitter era, as CJR’s Erika Fry observed at a debate during the Republican primary.

While such interpretations may be newsworthy, it’s valuable to separate them from a reporter or commentator’s judgment about what actually took place. So here’s a modest proposal to news outlets that takes Walter Shapiro’s advice to debate reporters a step further: Why not have blind debate coverage? For the next three presidential debates, send one of your reporters to a room with a TV and no Internet access and have him or her file a story on the debate before seeing anyone else’s take. I bet these accounts would frequently reach different conclusions from media hive mind. (I’m going to try this myself by staying off Twitter for the duration.)

Of course, I’m not optimistic that anyone will actually take me up on this idea. Even as political media becomes fractured along partisan lines, the impulse toward pack journalism remains deeply rooted. There’s a degree of professional safety for journalists whose reporting remains in step with the prevailing take on the news. At a broader level, news outlets little incentive to produce conflicting interpretations of an event; the authority of news coverage is implicitly premised on the idea that there is one objective set of facts to report. In reality, of course, news reporting is a process of selective interpretation—especially when it comes to debate reporting and commentary, which tend to focus on arbitrary and subjective stylistic judgments.

Legitimacy questions aside, however, it’s worth noting that the economic incentives that supported pack journalism are disappearing. Media outlets need to differentiate themselves in an increasingly crowded marketplace, and experimentation along the lines I’m suggesting could help us all learn something about the subjectivity of news judgment. Editors: take a chance!

*This sentence has been updated for clarity.

Related posts:

Debate advice: Turn off Twitter

What I saw at the South Carolina debate

Archives:

Archives: